Poster Session C

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Session: (2257–2325) SLE – Diagnosis, Manifestations, & Outcomes Poster III

2283: Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Among Patients Living with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Sweden: Coverage and Clinical Effectiveness

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

- AM

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Arthur Mageau1, Julia Simard2, Elisabet Svenungsson3 and Elizabeth Arkema4, 1Department of Medicine Solna, Clinical Epidemiology Division, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden / Internal Medicine Unit, Hopital Bichat, Paris, France, 2Department of Epidemiology & Population Health, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, 3Department of Medicine Solna, Unit of Rheumatology, Karolinska Institutet and Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, 4Department of Medicine Solna, Clinical Epidemiology Division, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Background/Purpose: Real-world data assessing the effectiveness of the anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination in patients living with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are currently lacking. We aimed to describe the uptake of the anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination in 2021 and to investigate its clinical effectiveness in SLE patients living in Sweden.

Methods: First, we described the cumulative incidence of first anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination among SLE patients and matched comparators living in Sweden on January 1, 2021 using the nationwide Swedish National Patient Register (NPR) and the National Vaccination Register. To assess vaccine effectiveness, we restricted the population to SLE patients and comparators i) with no COVID-19 diagnosis code before the 2nd vaccine dose and ii) who received two doses of anti-SARS-CoV2 mRNA vaccines before January 1st, 2022. The main outcome was a first hospitalization with COVID-19 as main diagnosis in the NPR. The secondary outcome was defined as first COVID-19 diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient care, as main or secondary diagnosis. Rates of main and secondary outcomes were compared between SLE patients and comparators. Multivariable-adjusted marginal Cox models estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (HR;95%CI) overall and stratified by immunosuppressive (IS) treatment received during the year before second vaccine dose.

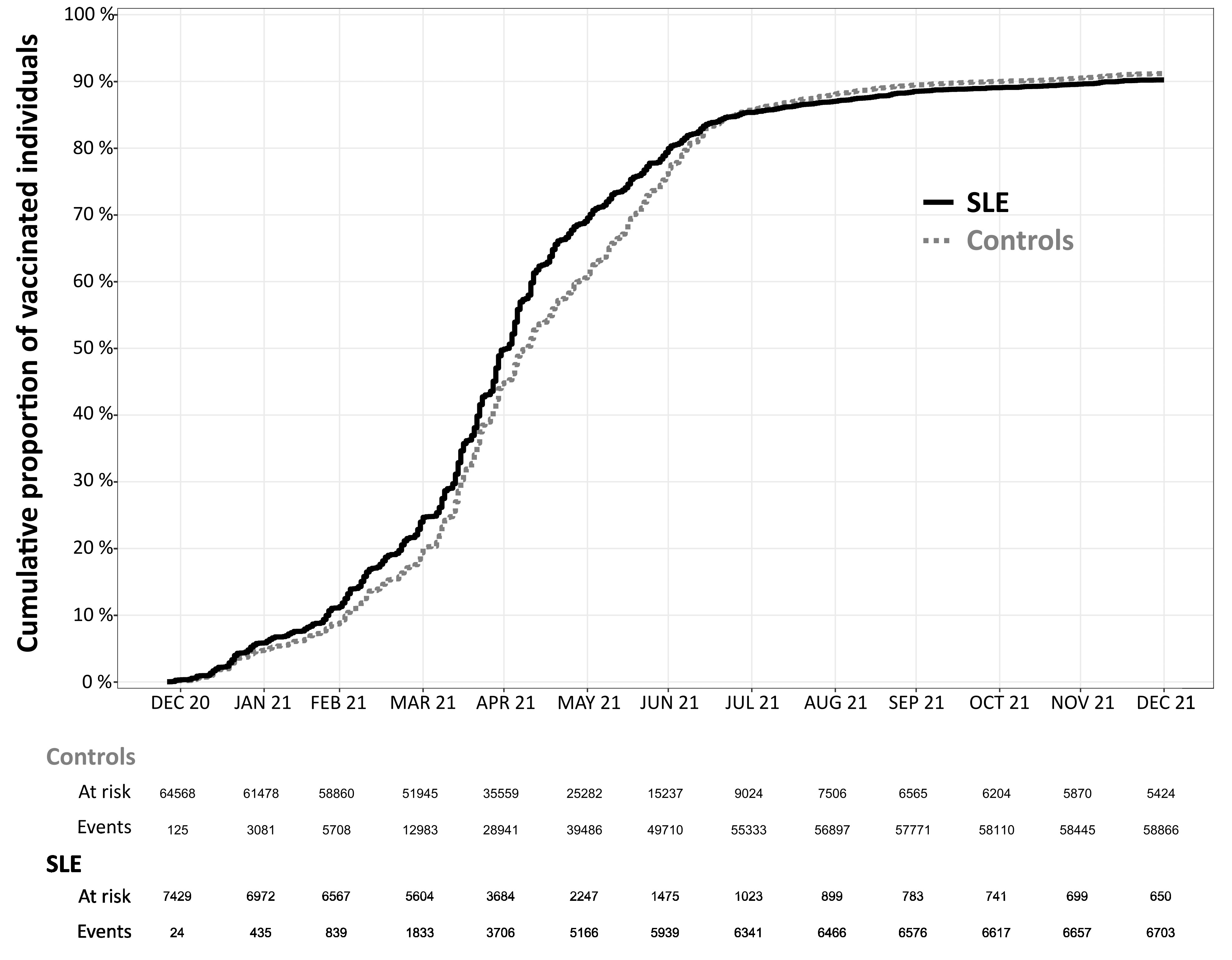

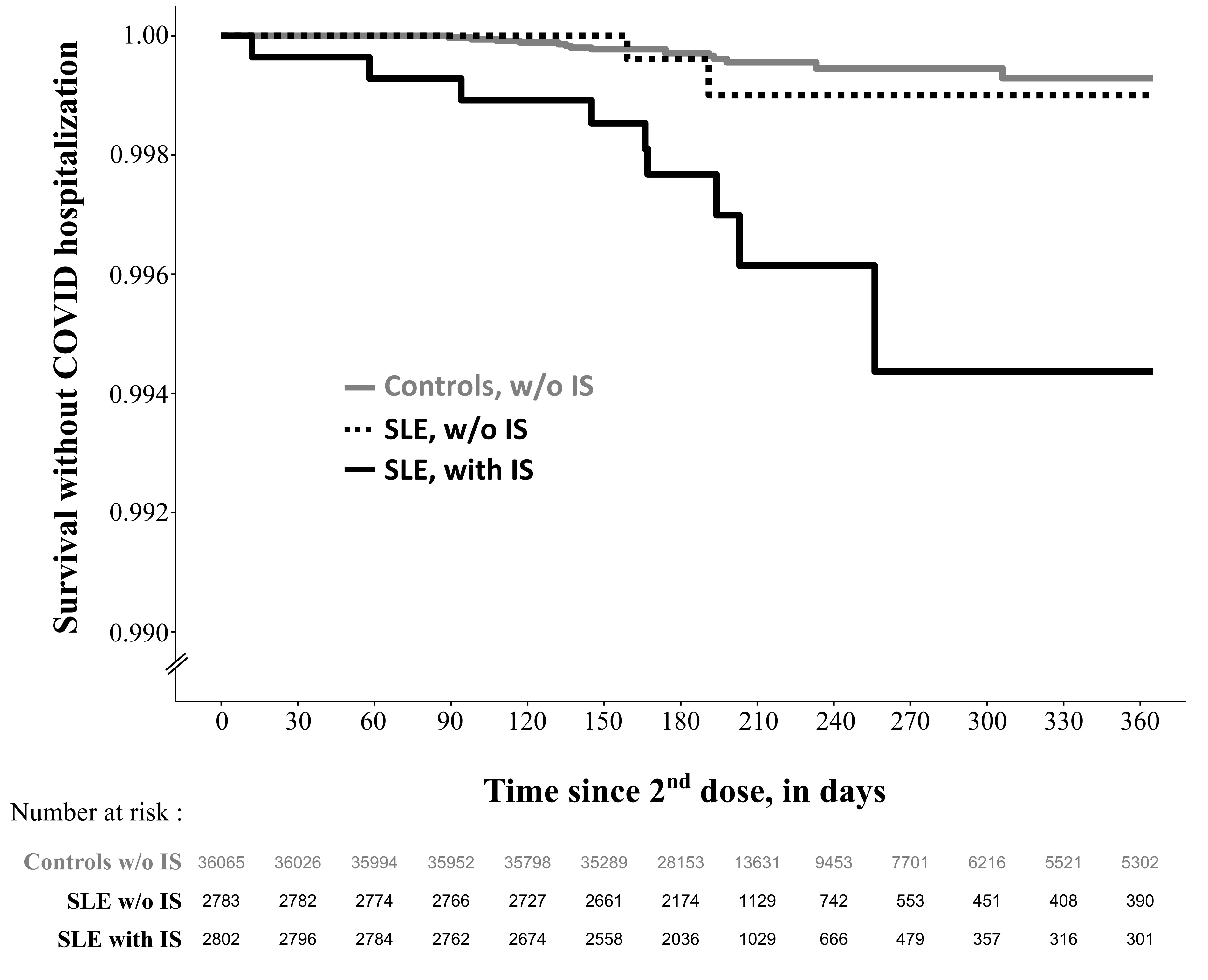

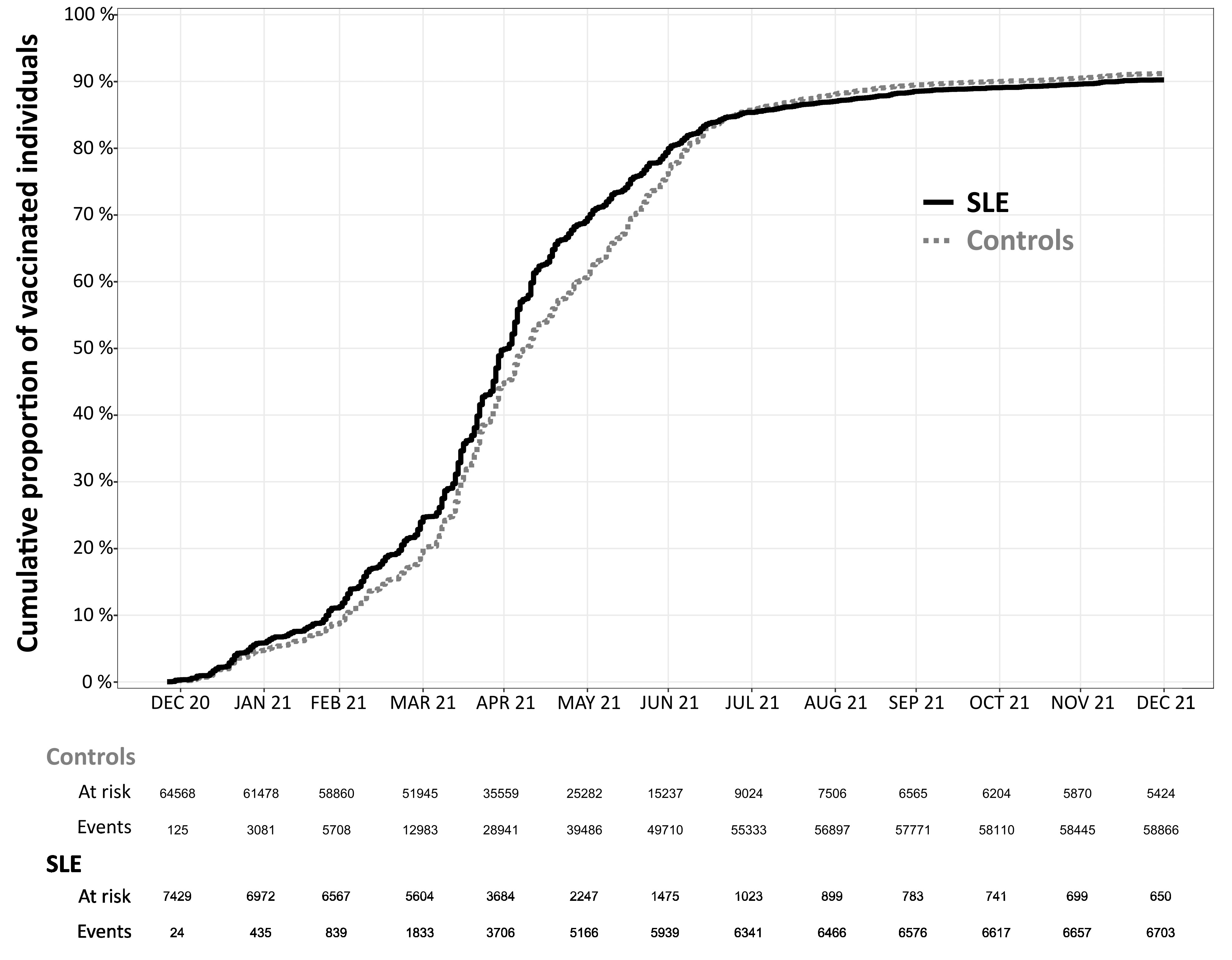

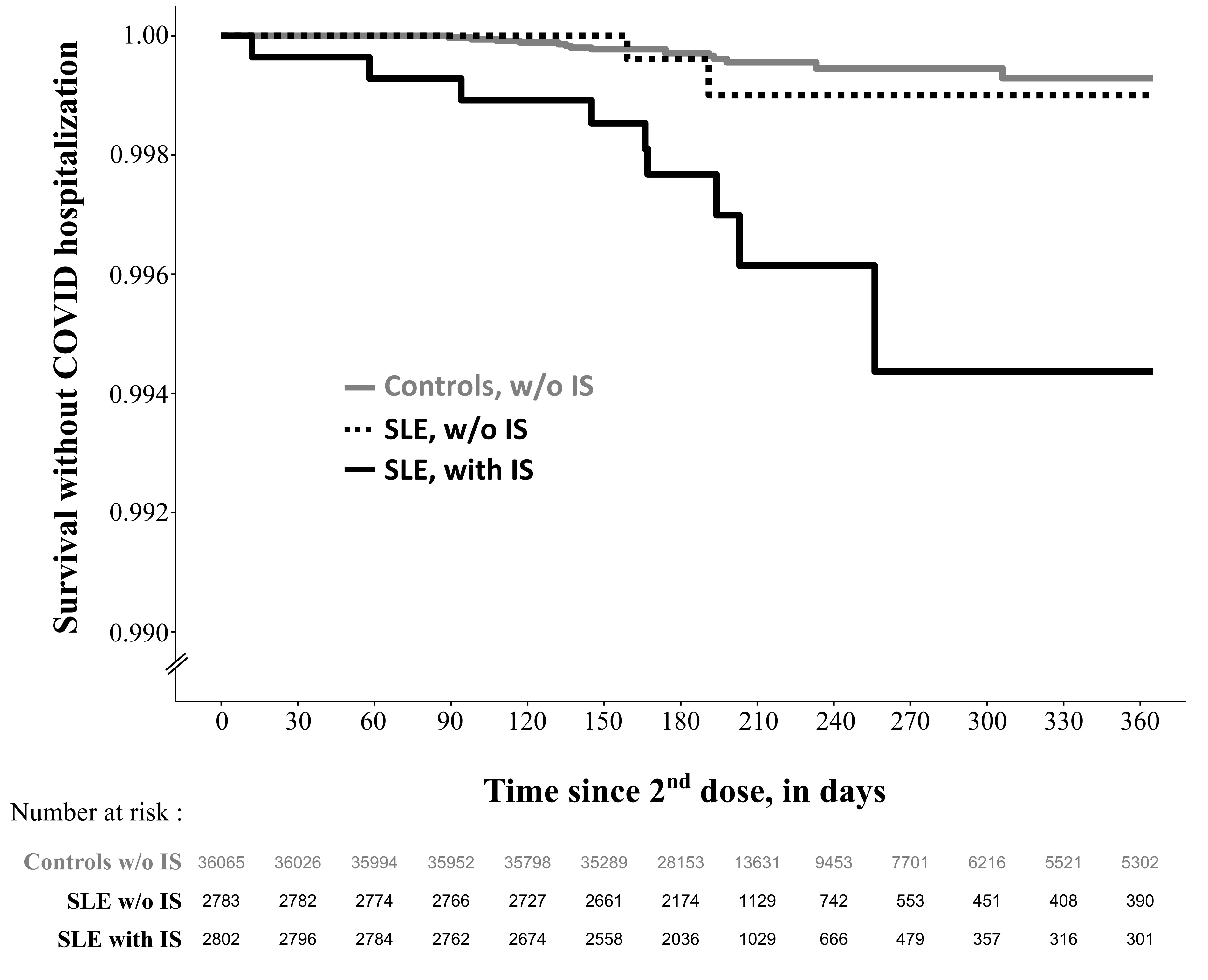

Results: To describe the vaccine coverage, we included 7,429 SLE patients and 64,568 comparators matched on age, sex and county of residence. Vaccination uptake was similar over 2021 between SLE patients and comparators (Figure 1). By the end of 2021, around 10% of both SLE and comparators received no vaccine doses. Among 5,585 SLE patients and 37,102 comparators included in the effectiveness analysis, we observed 11 hospitalizations with COVID-19 listed as the primary diagnosis in the SLE group and 20 in the comparator group (Table 1). SLE was associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 hospitalization (HR 3.47; 95%CI 1.63-7.39). Rates of events were higher in both groups using the secondary outcome (SLE N=29, comparators N=57) but the HR was similar to the main outcome (HR 3.58; 95%CI 2.30-5.59). There were 2,802 SLE patients (50.2%) who were treated with IS during the year before second vaccine dose. The HR of COVID-19 hospitalization was higher for IS-treated SLE (HR 7.03; 95%CI 3.00-16.5) than for IS-untreated (HR 1.50; 95%CI 0.34-6.60; Figure 2) compared to the general population.

Conclusion: Anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination coverage was similar between SLE patients and the general population in Sweden, but it could still be improved. Even though the incidence of post-vaccination COVID-19 hospitalization was very low, vaccine effectiveness was diminished in SLE patients and lowest in those treated with immunosuppressants.

A. Mageau: None; J. Simard: None; E. Svenungsson: None; E. Arkema: None.

Background/Purpose: Real-world data assessing the effectiveness of the anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination in patients living with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are currently lacking. We aimed to describe the uptake of the anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination in 2021 and to investigate its clinical effectiveness in SLE patients living in Sweden.

Methods: First, we described the cumulative incidence of first anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination among SLE patients and matched comparators living in Sweden on January 1, 2021 using the nationwide Swedish National Patient Register (NPR) and the National Vaccination Register. To assess vaccine effectiveness, we restricted the population to SLE patients and comparators i) with no COVID-19 diagnosis code before the 2nd vaccine dose and ii) who received two doses of anti-SARS-CoV2 mRNA vaccines before January 1st, 2022. The main outcome was a first hospitalization with COVID-19 as main diagnosis in the NPR. The secondary outcome was defined as first COVID-19 diagnosis in inpatient or outpatient care, as main or secondary diagnosis. Rates of main and secondary outcomes were compared between SLE patients and comparators. Multivariable-adjusted marginal Cox models estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (HR;95%CI) overall and stratified by immunosuppressive (IS) treatment received during the year before second vaccine dose.

Results: To describe the vaccine coverage, we included 7,429 SLE patients and 64,568 comparators matched on age, sex and county of residence. Vaccination uptake was similar over 2021 between SLE patients and comparators (Figure 1). By the end of 2021, around 10% of both SLE and comparators received no vaccine doses. Among 5,585 SLE patients and 37,102 comparators included in the effectiveness analysis, we observed 11 hospitalizations with COVID-19 listed as the primary diagnosis in the SLE group and 20 in the comparator group (Table 1). SLE was associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 hospitalization (HR 3.47; 95%CI 1.63-7.39). Rates of events were higher in both groups using the secondary outcome (SLE N=29, comparators N=57) but the HR was similar to the main outcome (HR 3.58; 95%CI 2.30-5.59). There were 2,802 SLE patients (50.2%) who were treated with IS during the year before second vaccine dose. The HR of COVID-19 hospitalization was higher for IS-treated SLE (HR 7.03; 95%CI 3.00-16.5) than for IS-untreated (HR 1.50; 95%CI 0.34-6.60; Figure 2) compared to the general population.

Conclusion: Anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination coverage was similar between SLE patients and the general population in Sweden, but it could still be improved. Even though the incidence of post-vaccination COVID-19 hospitalization was very low, vaccine effectiveness was diminished in SLE patients and lowest in those treated with immunosuppressants.

Figure 1: Uptake of the anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccine in SLE patients and matched comparators in Sweden, December 2020 to December 2021

Table 1: SLE patients and matched general population comparators who received 2 doses of mRNA anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccine in Sweden before January 1st, 2022.

Figure 2: Survival without COVID-19 as a main diagnosis in inpatient care January 1st, 2021 among SLE patients treated with immunosuppressants, SLE patients not treated with immunosuppressants and comparators from general population who received 2 doses of mRNA anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccine in Sweden before January 1st, 2022.

A. Mageau: None; J. Simard: None; E. Svenungsson: None; E. Arkema: None.