Poster Session B

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Session: (1488–1512) SLE – Treatment Poster II

1509: Calcineurin Inhibitors for Treatment of Lupus Nephritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Monday, November 13, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

- GF

Gabriel Figueroa-Parra, MD

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, MN, United StatesDisclosure information not submitted.

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Gabriel Figueroa-Parra1, Maria Cuellar-Gutierrez1, Mariana Gonzalez-Trevino1, Larry J. Prokop2, M. Hassan Murad3 and Ali Duarte-Garcia4, 1Division of Rheumatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, 2Mayo Clinic Libraries, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, 3Evidence-based Practice Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, 4Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Background/Purpose: The current recommendations for the treatment of LN consider as the standard of care (SoC) the use of MMF or CYC. Considering the expanding evidence for the use of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) in patients with LN, we aimed to summarize and assess the efficacy and safety of CNI compared to the current SoC for the treatment of patients with LN.

Methods: We comprehensively searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and Scopus from each database's inception to January 19, 2023. Studies were eligible if they included (P) patients with biopsy-proven LN, (I) compared CNI (voclosporin, tacrolimus, and CSA) alone or in combination with other immunosuppressors against (C) the SoC (MMF or CYC), (O) for efficacy (complete and partial renal response [CR and PR, respectively]) and safety (death, infections, gastrointestinal adverse effects [GIAE], cytopenias). Exclusion criteria were patients with SLE without biopsy-proven LN, non-pharmacological interventions, observational studies, and non-RCTs. We used the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials 2. We expressed the results as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used random-effect models and assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection and by using the I2 and Chi2 tests. We performed subgroup analyses to test for interactions based on CNI and SoC.

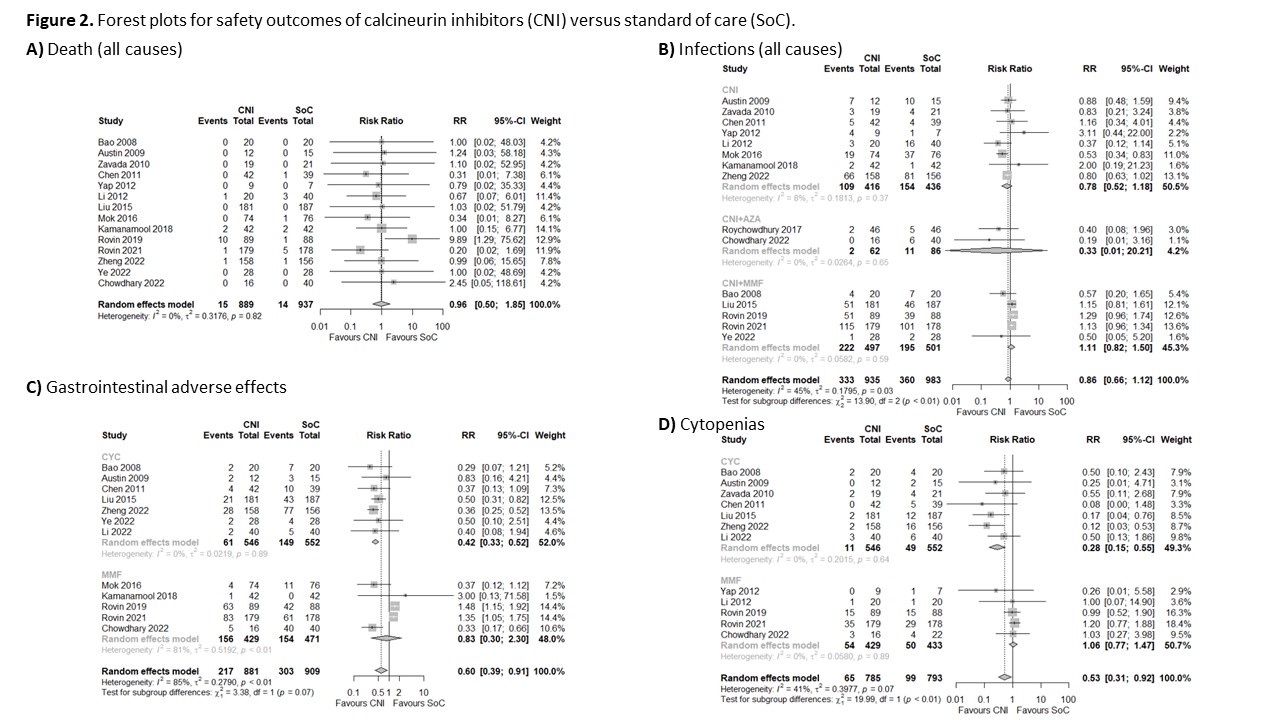

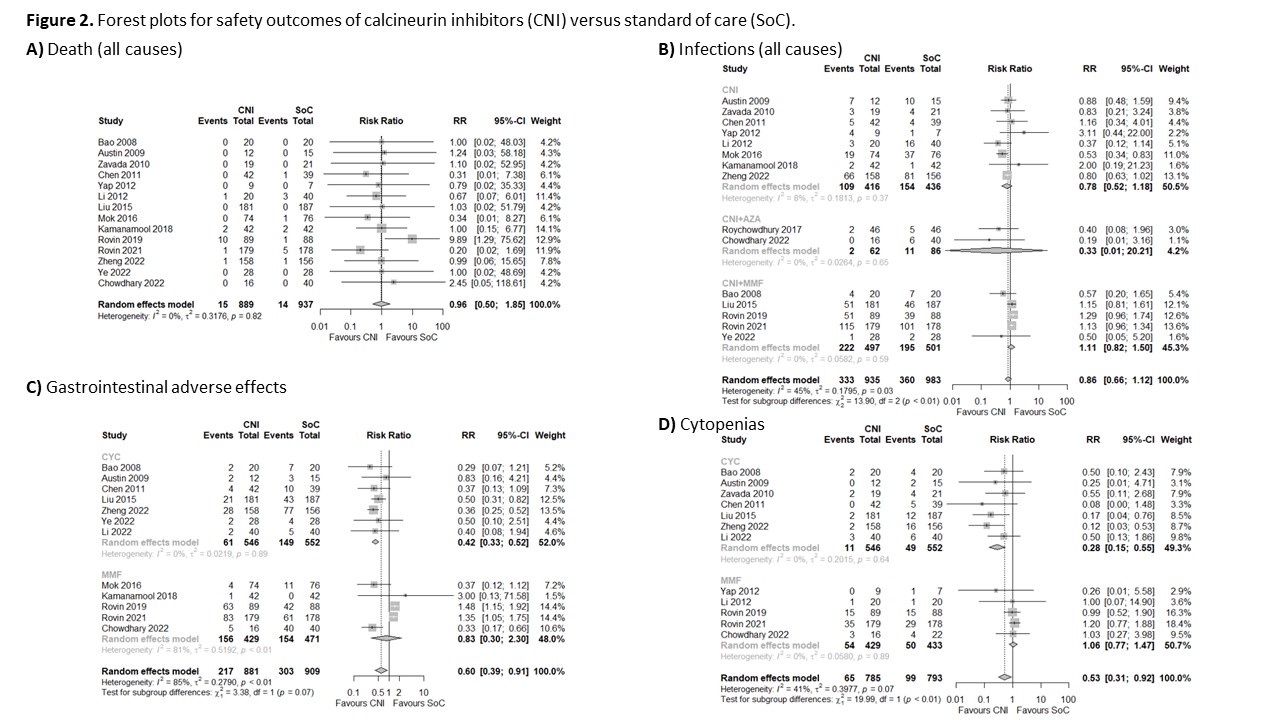

Results: We included 1998 patients with LN (16 RCTs), 975 patients who received CNI, and 1023 patients who received SoC (433 MMF and 590 CYC). The overall risk of bias was low in nine studies, five studies showed some concerns, and two had a high risk of bias (Table 1). Patients with LN treated with CNI for induction of remission may be more likely to achieve CR at 6 (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.17-1.95; I2 = 21%; 12 RCTs; 1791 patients; Figure 1A) and 12 months (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.06-2.21; I2 = 60%; 8 RCTs; 1189 patients; Figure 1B) than those treated with the SoC. CNI alone (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.22-1.63; I2 = 0%; 5 RCTs; 852 patients) and CNI+MMF (RR 2.14, 95% CI 1.10-4.17; I2 = 15%; 5 RCTs; 998 patients) were more likely to achieved CR at 6 months against the SoC. Only CNI+MMF was better than SoC at 12 months (RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.27-2.21; I2 = 31%; 5 RCTs; 998 patients). CNI also showed a higher probability of achieving PR at 6 and 12 months compared with the SoC (Figure 1C and 1D). We did not find a difference in the risk of death between patients treated with CNI or SoC (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.50-1.85; I2 = 0%; 14 RCTs; 1826 patients; Figure 2A). Patients with LN treated with CNI showed a similar infection risk to those patients treated with the SoC (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.66-1.22; I2 = 45%; 15 RCTs, 1918 patients; Figure 2B). There was a difference given by the subgroups of CNI (p< 0.01), but not according to the SoC (p=0.99). We found a lower risk of GIAE (RR 0.6, 95% CI 0.39-0.91; I2 = 85%; 12 RCTs; 1790 patients; Figure 1C) and cytopenias (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31-0.87; I2 = 41%; 12 RCTs; 1616 patients; Figure 1D) among patients treated with CNI than those treated with the SoC.

Conclusion: Patients with LN treated with CNI for the induction of remission may have better response compared with MMF or CYC. CNI might be considered as equally safe in mortality and infections as the SoC. Possibly CNI might have less GIAE and cytopenias than the SoC, particularly compared with CYC.

.jpg)

G. Figueroa-Parra: None; M. Cuellar-Gutierrez: None; M. Gonzalez-Trevino: None; L. Prokop: None; M. Murad: None; A. Duarte-Garcia: None.

Background/Purpose: The current recommendations for the treatment of LN consider as the standard of care (SoC) the use of MMF or CYC. Considering the expanding evidence for the use of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) in patients with LN, we aimed to summarize and assess the efficacy and safety of CNI compared to the current SoC for the treatment of patients with LN.

Methods: We comprehensively searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and Scopus from each database's inception to January 19, 2023. Studies were eligible if they included (P) patients with biopsy-proven LN, (I) compared CNI (voclosporin, tacrolimus, and CSA) alone or in combination with other immunosuppressors against (C) the SoC (MMF or CYC), (O) for efficacy (complete and partial renal response [CR and PR, respectively]) and safety (death, infections, gastrointestinal adverse effects [GIAE], cytopenias). Exclusion criteria were patients with SLE without biopsy-proven LN, non-pharmacological interventions, observational studies, and non-RCTs. We used the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials 2. We expressed the results as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used random-effect models and assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection and by using the I2 and Chi2 tests. We performed subgroup analyses to test for interactions based on CNI and SoC.

Results: We included 1998 patients with LN (16 RCTs), 975 patients who received CNI, and 1023 patients who received SoC (433 MMF and 590 CYC). The overall risk of bias was low in nine studies, five studies showed some concerns, and two had a high risk of bias (Table 1). Patients with LN treated with CNI for induction of remission may be more likely to achieve CR at 6 (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.17-1.95; I2 = 21%; 12 RCTs; 1791 patients; Figure 1A) and 12 months (RR 1.53, 95% CI 1.06-2.21; I2 = 60%; 8 RCTs; 1189 patients; Figure 1B) than those treated with the SoC. CNI alone (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.22-1.63; I2 = 0%; 5 RCTs; 852 patients) and CNI+MMF (RR 2.14, 95% CI 1.10-4.17; I2 = 15%; 5 RCTs; 998 patients) were more likely to achieved CR at 6 months against the SoC. Only CNI+MMF was better than SoC at 12 months (RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.27-2.21; I2 = 31%; 5 RCTs; 998 patients). CNI also showed a higher probability of achieving PR at 6 and 12 months compared with the SoC (Figure 1C and 1D). We did not find a difference in the risk of death between patients treated with CNI or SoC (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.50-1.85; I2 = 0%; 14 RCTs; 1826 patients; Figure 2A). Patients with LN treated with CNI showed a similar infection risk to those patients treated with the SoC (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.66-1.22; I2 = 45%; 15 RCTs, 1918 patients; Figure 2B). There was a difference given by the subgroups of CNI (p< 0.01), but not according to the SoC (p=0.99). We found a lower risk of GIAE (RR 0.6, 95% CI 0.39-0.91; I2 = 85%; 12 RCTs; 1790 patients; Figure 1C) and cytopenias (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31-0.87; I2 = 41%; 12 RCTs; 1616 patients; Figure 1D) among patients treated with CNI than those treated with the SoC.

Conclusion: Patients with LN treated with CNI for the induction of remission may have better response compared with MMF or CYC. CNI might be considered as equally safe in mortality and infections as the SoC. Possibly CNI might have less GIAE and cytopenias than the SoC, particularly compared with CYC.

.jpg)

G. Figueroa-Parra: None; M. Cuellar-Gutierrez: None; M. Gonzalez-Trevino: None; L. Prokop: None; M. Murad: None; A. Duarte-Garcia: None.