Poster Session A

Infection-related rheumatic syndromes

Session: (0196–0228) Infection-related Rheumatic Disease Poster

0221: Post-COVID-19 Autoimmune Serologies and Immunophenotypes

Sunday, November 12, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

- EO

Emily Oakes, BA

Brigham and Women's Hospital

Boston, MA, United StatesDisclosure information not submitted.

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Emily G. Oakes1, Katherine Buhler2, Ifeoluwakiisi Adejoorin1, Kathryne Marks1, Eilish Dillon1, Jack Ellrodt1, Jeong Yee1, Deepak Rao1, May Choi3 and Karen Costenbader4, 1Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, 2University of Calgary; Cumming School of Medicine, Calgary, AB, Canada, 3University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 4Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Background/Purpose: Autoimmunity after COVID-19 infection has been reported. We examined connective tissue disease (CTD) symptoms and autoantibodies, SARS-CoV-2 serologies, and T and B cell immunophenotypes (found in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and scleroderma in past studies), by the early vs. late COVID-19 pandemic waves. We hypothesized that patients who had COVID in earlier (3/1/2020- 1/31/2021) vs. later (2/1/2021-9/1/2021) waves would have higher prevalence of new CTD symptoms, autoantibodies, and abnormal immunophenotypes.

Methods: We identified patients COVID-19 PCR positive from 3/1/2020-9/1/2021 in the Mass General Brigham system. Eligible participants ≥18 years old and ≥1-month post-COVID-19 with no prior history of CTD received the CTD Screening Questionnaire (CSQ; Karlson EW, 1995) to complete. Subjects who returned questionnaires were invited for a blood draw. Subjects were tested for 27 autoimmune and 3 SARS-CoV-2 serologies, and for T peripheral helper cells (TpH), T follicular helper cells (TfH), age-related B cells (ABCs), and plasmablasts (PBs) proportions by flow cytometry. We tested for associations between clinical variables, serologies, and immunophenotypes (% total CD4 T cells for TpH and TfH; % total CB19 B cells for ABC and PB) using t-tests, Chi-square, and multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, race, sex. A heatmap of the multidimensional data was generated to elucidate underlying patterns.

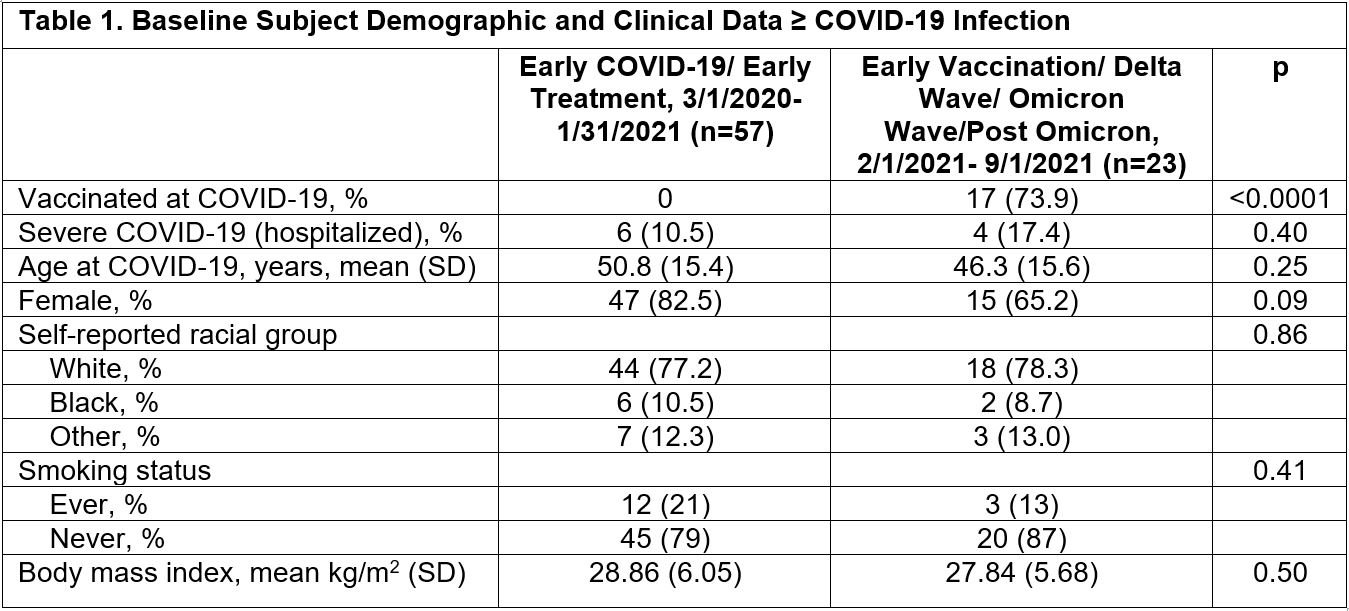

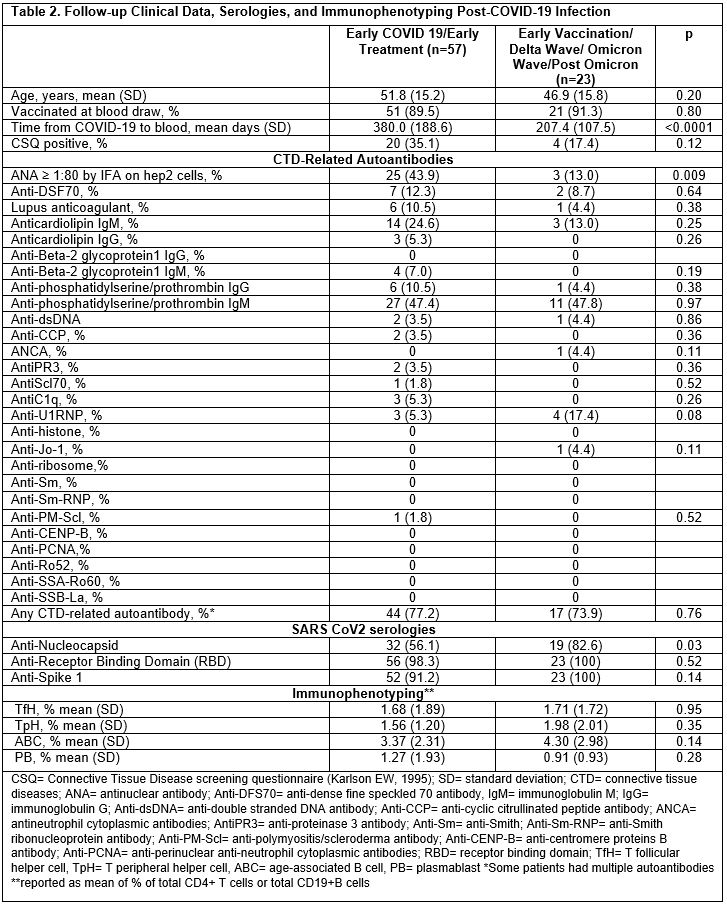

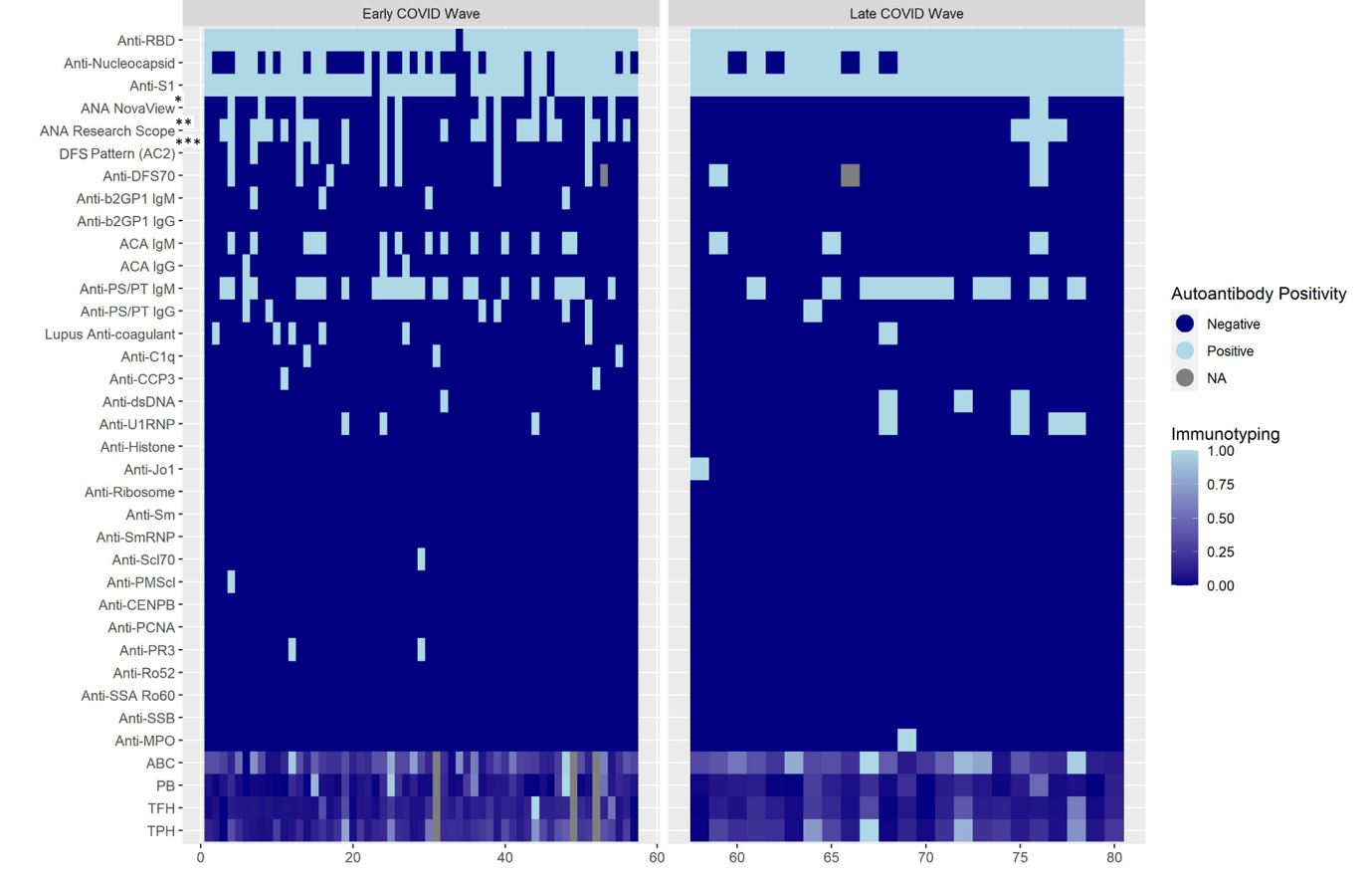

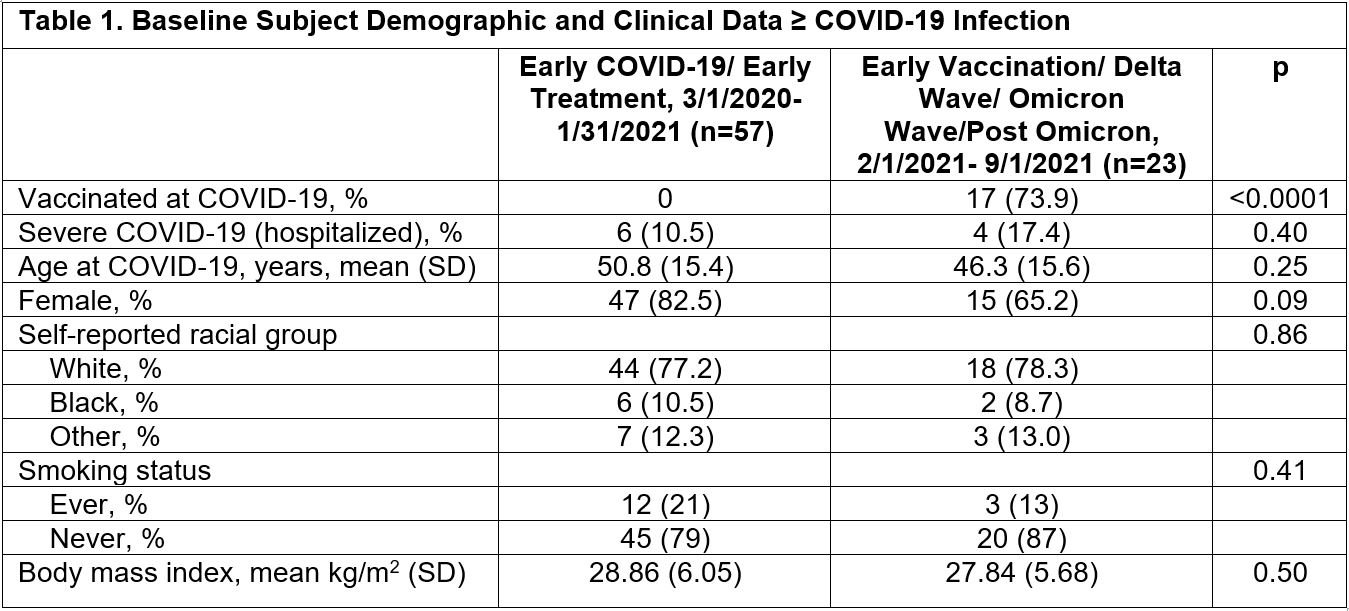

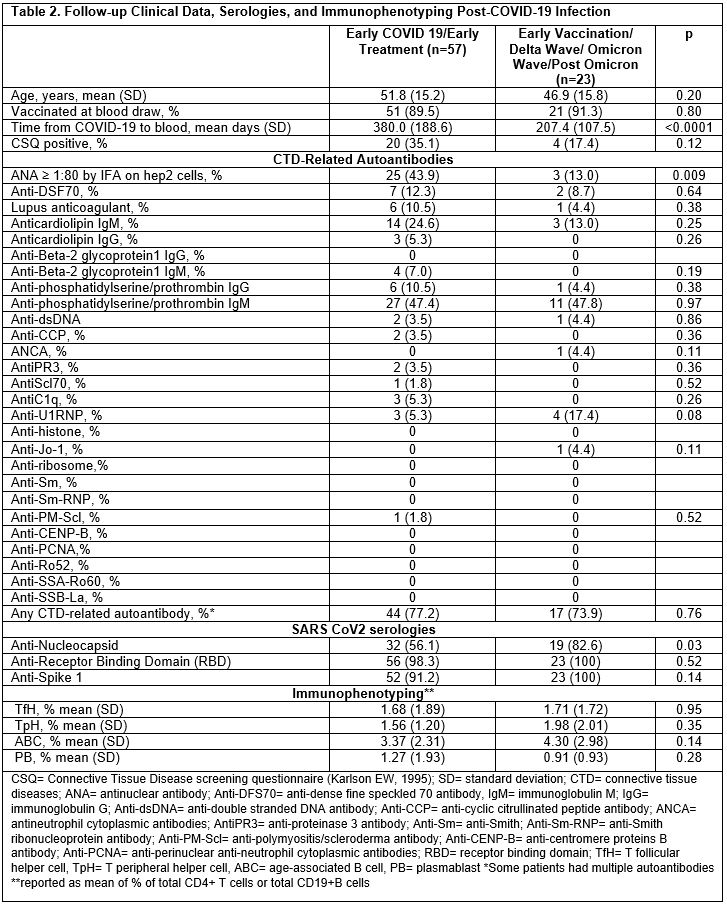

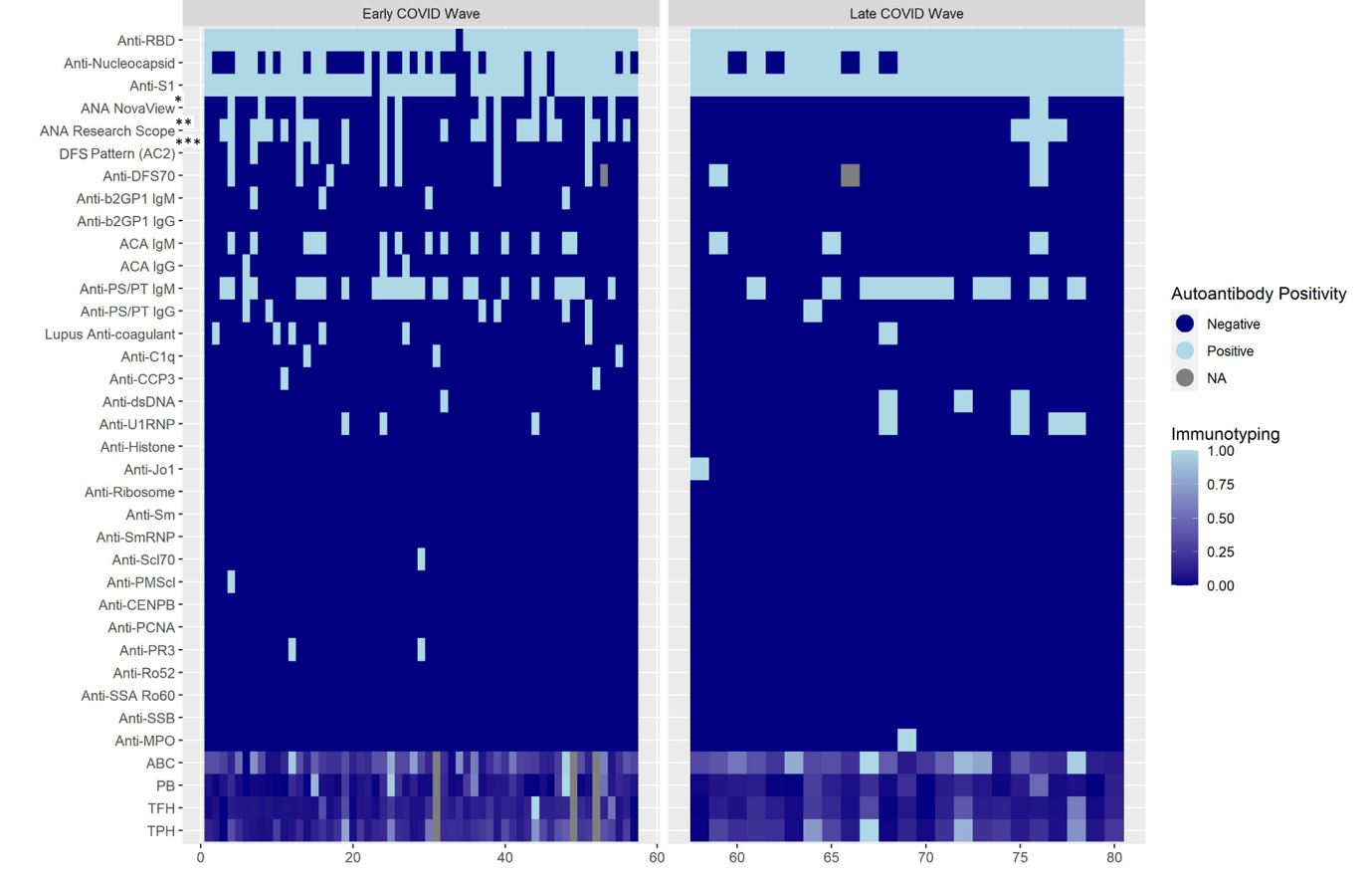

Results: 324 of 2,935 screening questionnaires (11%) were returned; 80 eligible subjects participated. Baseline demographics and clinical data are shown in Table 1 by early vs. late COVID-19 wave. 17 subjects were vaccinated at infection, all in the later pandemic; 10 subjects were hospitalized for COVID-19. Among those in earlier vs. later COVID waves, a higher proportion were CSQ+ (35% vs. 17%, p 0.12), and more were ANA+ (44% vs. 13%, p 0.009) (Table 2). Lupus anticoagulant was positive in 11% of early vs. 4% of late COVID, p 0.38. Having ≥1 positive autoantibody was found in 77% of early vs. 74% of later COVID subjects, p 0.76. After adjustment for age, race, and sex, having early (vs. late) COVID variants was associated with increased risk of ANA positivity (MV OR 4.55, 95%CI 1.16, 16.67). The heatmap revealed more variety of autoantibody positivity in early COVID, with more antibodies to cardiolipin IgG, B2GP1 IgM, C1q, CCP3, PMScl, PR3, Scl70, while Jo-1 and MPO were only present in later COVID waves. No clear patterns were seen in T and B cell phenotypes (Figure 1).

Conclusion: Although a small study without controls, infection in earlier vs. later COVID was associated with more ANA positivity and autoimmune rheumatic disease symptoms (latter non-significantly). Heatmap analyses elucidated increased prevalence of other autoantibody positivity in the earlier wave. These results raise the possibility that more virulent SARS-CoV-2 strains circulating in the early pandemic and pre-vaccine availability were more immunogenic and more likely to result in autoantibody production.

E. Oakes: None; K. Buhler: None; I. Adejoorin: None; K. Marks: None; E. Dillon: None; J. Ellrodt: None; J. Yee: None; D. Rao: AstraZeneca, 2, Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2, 5, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 2, Hifibio, 2, Janssen, 5, Merck, 5, Scipher Medicine, 2; M. Choi: AbbVie/Abbott, 2, 6, Amgen, 2, 6, AstraZeneca, 2, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 2, 6, Celgene, 2, 6, Eli Lilly, 2, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 2, Janssen, 2, 6, Mallinckrodt, 2, Merck/MSD, 2, MitogenDx, 2, Organon, 6, Pfizer, 2, 6, Roche, 2, Werfen, 2; K. Costenbader: Amgen, 2, 5, AstraZeneca, 5, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 2, Cabaletta, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, Exagen Diagnostics, 5, Gilead, 5, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 2, 5, Janssen, 2, 5.

Background/Purpose: Autoimmunity after COVID-19 infection has been reported. We examined connective tissue disease (CTD) symptoms and autoantibodies, SARS-CoV-2 serologies, and T and B cell immunophenotypes (found in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and scleroderma in past studies), by the early vs. late COVID-19 pandemic waves. We hypothesized that patients who had COVID in earlier (3/1/2020- 1/31/2021) vs. later (2/1/2021-9/1/2021) waves would have higher prevalence of new CTD symptoms, autoantibodies, and abnormal immunophenotypes.

Methods: We identified patients COVID-19 PCR positive from 3/1/2020-9/1/2021 in the Mass General Brigham system. Eligible participants ≥18 years old and ≥1-month post-COVID-19 with no prior history of CTD received the CTD Screening Questionnaire (CSQ; Karlson EW, 1995) to complete. Subjects who returned questionnaires were invited for a blood draw. Subjects were tested for 27 autoimmune and 3 SARS-CoV-2 serologies, and for T peripheral helper cells (TpH), T follicular helper cells (TfH), age-related B cells (ABCs), and plasmablasts (PBs) proportions by flow cytometry. We tested for associations between clinical variables, serologies, and immunophenotypes (% total CD4 T cells for TpH and TfH; % total CB19 B cells for ABC and PB) using t-tests, Chi-square, and multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, race, sex. A heatmap of the multidimensional data was generated to elucidate underlying patterns.

Results: 324 of 2,935 screening questionnaires (11%) were returned; 80 eligible subjects participated. Baseline demographics and clinical data are shown in Table 1 by early vs. late COVID-19 wave. 17 subjects were vaccinated at infection, all in the later pandemic; 10 subjects were hospitalized for COVID-19. Among those in earlier vs. later COVID waves, a higher proportion were CSQ+ (35% vs. 17%, p 0.12), and more were ANA+ (44% vs. 13%, p 0.009) (Table 2). Lupus anticoagulant was positive in 11% of early vs. 4% of late COVID, p 0.38. Having ≥1 positive autoantibody was found in 77% of early vs. 74% of later COVID subjects, p 0.76. After adjustment for age, race, and sex, having early (vs. late) COVID variants was associated with increased risk of ANA positivity (MV OR 4.55, 95%CI 1.16, 16.67). The heatmap revealed more variety of autoantibody positivity in early COVID, with more antibodies to cardiolipin IgG, B2GP1 IgM, C1q, CCP3, PMScl, PR3, Scl70, while Jo-1 and MPO were only present in later COVID waves. No clear patterns were seen in T and B cell phenotypes (Figure 1).

Conclusion: Although a small study without controls, infection in earlier vs. later COVID was associated with more ANA positivity and autoimmune rheumatic disease symptoms (latter non-significantly). Heatmap analyses elucidated increased prevalence of other autoantibody positivity in the earlier wave. These results raise the possibility that more virulent SARS-CoV-2 strains circulating in the early pandemic and pre-vaccine availability were more immunogenic and more likely to result in autoantibody production.

Figure 1. Hierarchical heatmap clustering of autoantibody and immune profile results among 80 subjects following COVID-19 infection stratified by COVID-19 wave (early vs. late). ANA= antinuclear antibody; Anti-DFS70= anti-dense fine speckled 70 antibody, IgM= immunoglobulin M; IgG= immunoglobulin G; Anti-dsDNA= anti-double stranded DNA antibody; Anti-CCP= anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody; ANCA= antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; AntiPR3= anti-proteinase 3 antibody; Anti-Sm= anti-Smith; Anti-Sm-RNP= anti-Smith ribonucleoprotein antibody; Anti-PM-Scl= anti-polymyositis/scleroderma antibody; Anti-CENP-B= anti-centromere proteins B antibody; Anti-PCNA= anti-perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; RBD= receptor binding domain; TfH= T follicular helper cell, TpH= T peripheral helper cell, ABC= age-associated B cell, PB= plasmablast; *ANA NovaView is read by automated digital immunofluorescence assay microscope, **ANA research scope is manual ANA interpretation by experienced laboratory technician, ***DFS AC-2 is nuclear dense fine speckled antinuclear antibody pattern associated with anti-DFS70 antibody

E. Oakes: None; K. Buhler: None; I. Adejoorin: None; K. Marks: None; E. Dillon: None; J. Ellrodt: None; J. Yee: None; D. Rao: AstraZeneca, 2, Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2, 5, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 2, Hifibio, 2, Janssen, 5, Merck, 5, Scipher Medicine, 2; M. Choi: AbbVie/Abbott, 2, 6, Amgen, 2, 6, AstraZeneca, 2, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 2, 6, Celgene, 2, 6, Eli Lilly, 2, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 2, Janssen, 2, 6, Mallinckrodt, 2, Merck/MSD, 2, MitogenDx, 2, Organon, 6, Pfizer, 2, 6, Roche, 2, Werfen, 2; K. Costenbader: Amgen, 2, 5, AstraZeneca, 5, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 2, Cabaletta, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, Exagen Diagnostics, 5, Gilead, 5, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 2, 5, Janssen, 2, 5.