Poster Session A

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Session: (0582–0608) SLE – Treatment Poster I

0606: Risk of Damage Progression with Belimumab versus Oral Immunosuppressant Use in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Sunday, November 12, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

April Jorge, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, MA, United StatesDisclosure(s): No financial relationships with ineligible companies to disclose

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

April Jorge1, Baijun Zhou1, Yuqing Zhang2 and Hyon K. Choi3, 1Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, 2Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, 3Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Lexington, MA

Background/Purpose: Belimumab was approved for the treatment of non-renal SLE in 2011 and has been previously associated with a lower risk of damage progression when compared with prior 'usual care.' We sought to determine the risk of damage progression with belimumab versus alternative SLE immunosuppressants in a contemporary real world setting.

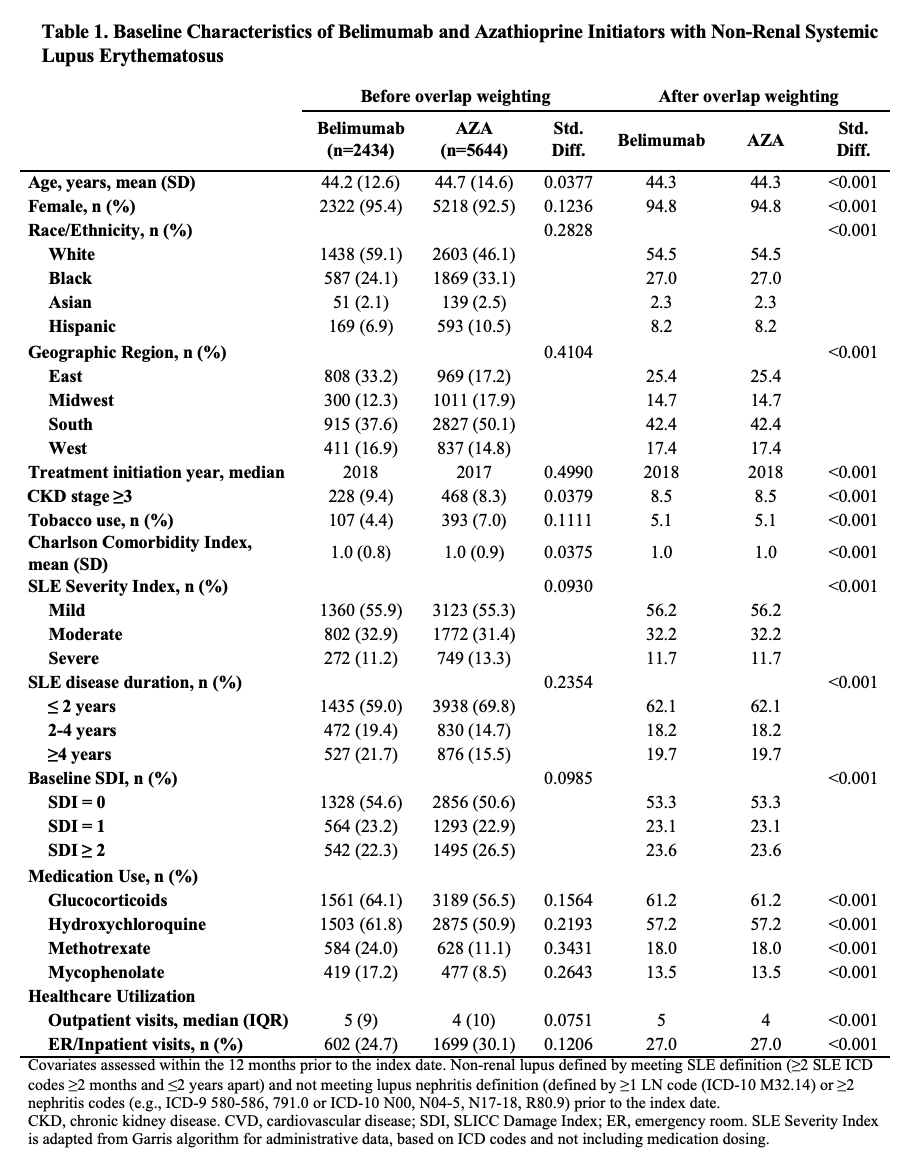

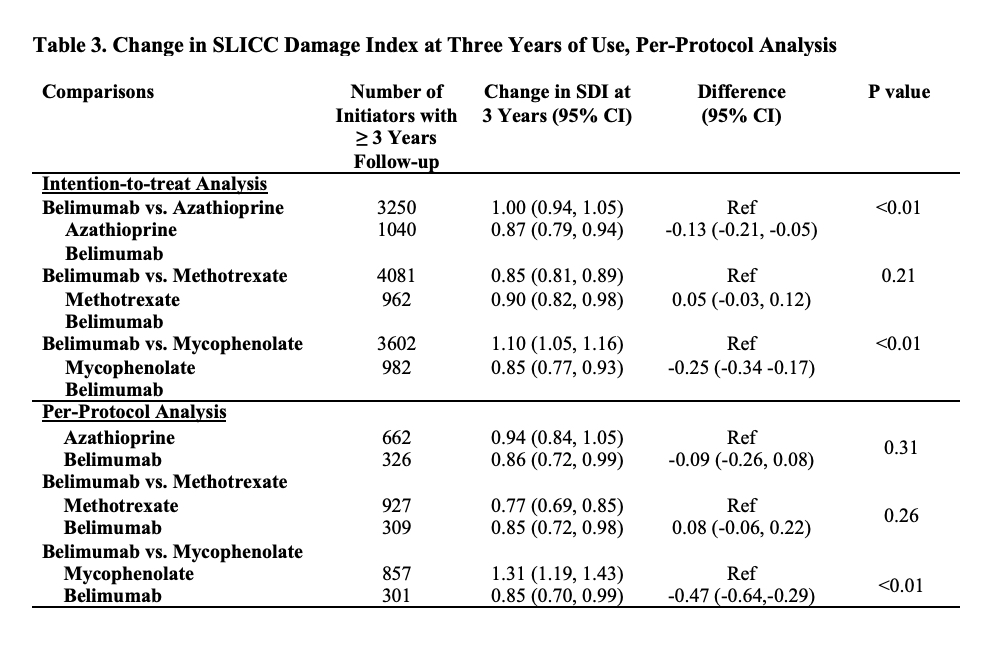

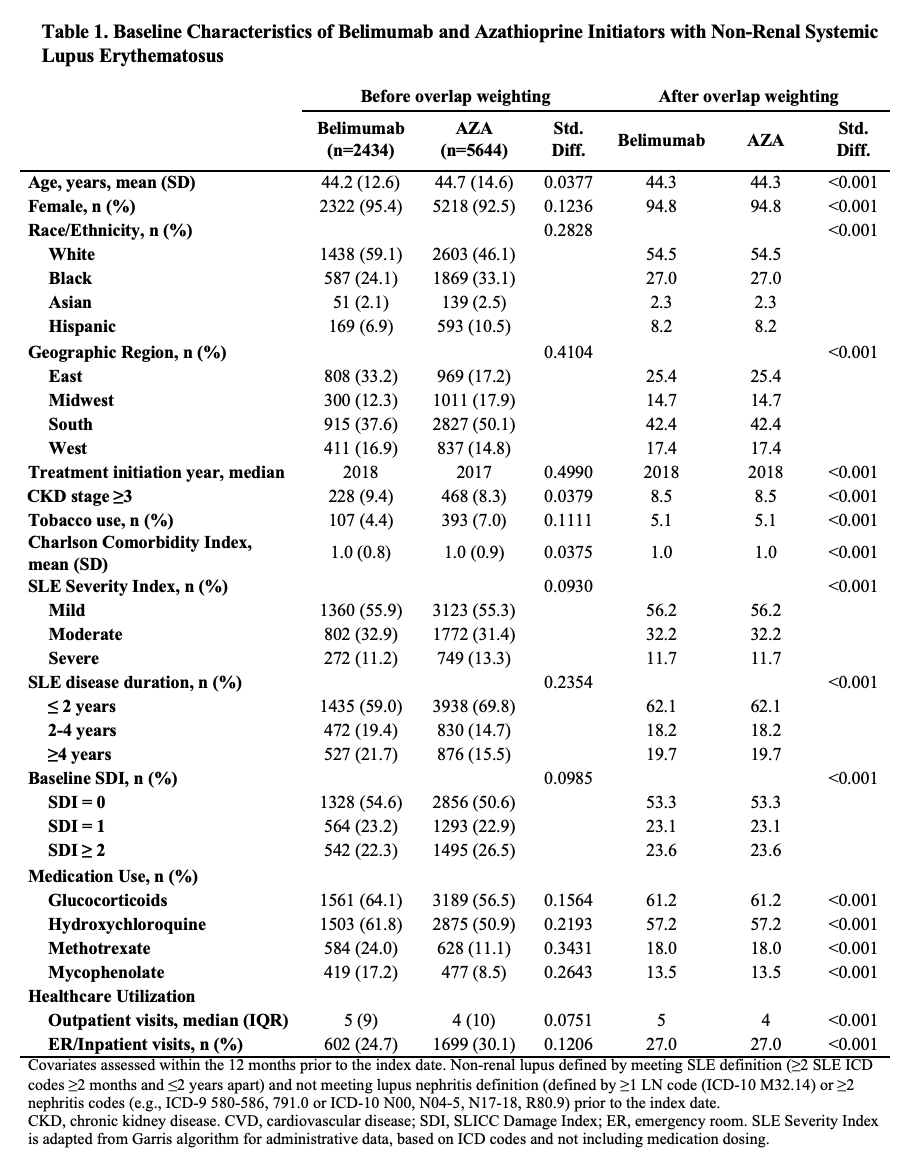

Methods: We identified all adults with SLE (defined by ≥2 ICD codes >30 days and < 2 years apart) in a United States multi-center electronic health record (EHR) database, TriNetX. We identified all patients who initiated belimumab, azathioprine (AZA), methotrexate (MTX), or mycophenolate (MMF) between 3/2011 and 8/2021. We designed and emulated a pragmatic target trial to compare the risk of damage progression with initiation of belimumab vs. AZA, belimumab vs. MTX, and belimumab vs MMF. For each comparison, eligible patients had never used the direct comparator but could have used other immunosuppressants and did not have lupus nephritis prior to the index date of treatment initiation. To emulate randomization, we used propensity score overlap weighting to balance baseline covariates, including demographics, geographic region, treatment initiation year, comorbidities including CKD, congestive heart failure, obesity, cardiovascular disease, the Charlson comorbidity index, tobacco use, SLE severity index (Garris C. J Med Econ 2013), SLE disease duration, baseline SLICC damage index score (categorized as 0, 1, or ≥2), medication use including glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, and other immunosuppressants, and healthcare utilization. We assessed the outcome of damage progression defined by an increase in the SLICC damage index (SDI), which was adapted to administrative data using ICD codes. We conducted an intention-to-treat analysis and a per-protocol analysis using pooled logistic regression where we adjusted for adherence to assigned treatment with inverse probability of treatment weighting. We also assessed the mean change in the SDI at three years among patients with ≥3 years of follow-up using linear regression.

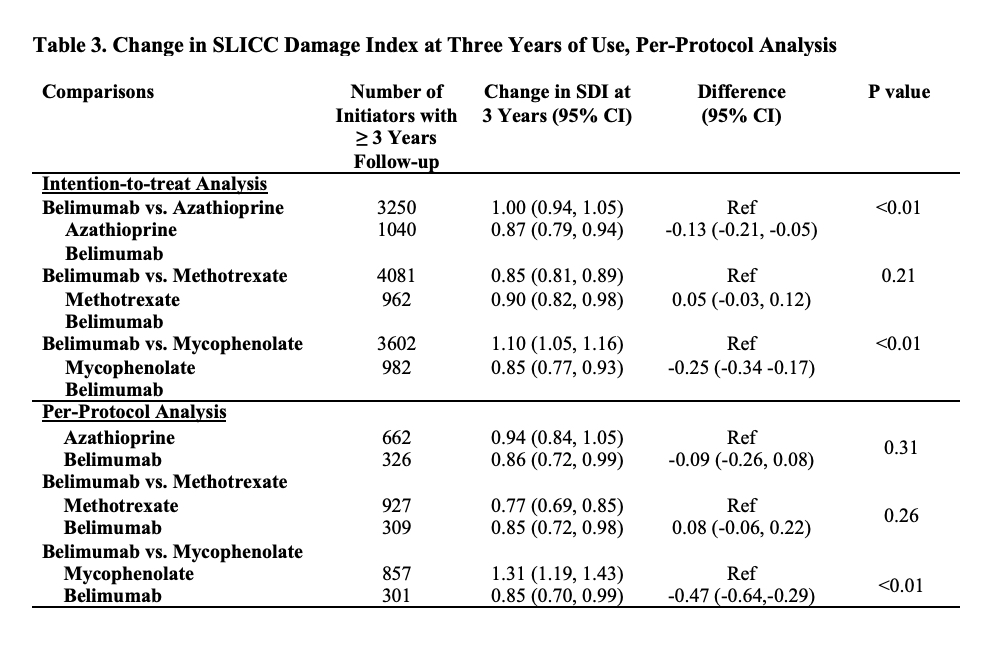

Results: We compared 2,434 and 5,644 initiators of belimumab and AZA, (Table 1), 2,163 and 7,224 initiators of belimumab and MTX, and 2,431 and 6,350 initiators of belimumab and MMF, respectively. In each comparison, covariates were balanced after propensity score overlap weighting. 95% were female; the mean age was 44 years. 53% had a baseline SDI of zero. After 5 years, over 41% in each treatment group developed ≥1 new damage item on the SDI. The risk of damage progression was lower with belimumab than mycophenolate (HR 0.74 [95% CI 0.67-0.83]; Table 2), but there was no difference in the risk of damage progression between belimumab and AZA or belimumab and MTX. Similarly, belimumab was associated with a lower 3-year change in SDI when compared with MMF, but there was no difference when compared with AZA and MTX (Table 3).

Conclusion: In this real world EHR-based SLE cohort, after accounting for baseline covariates associated with the risk of organ damage, belimumab was associated with a lower risk of damage progression than MMF but not AZA or MTX use. Limitations include the use of administrative claims to identify components of the SDI.

.jpg)

A. Jorge: None; B. Zhou: None; Y. Zhang: None; H. Choi: Ani, 2, Horizon, 2, 5, LG, 2, Protalix, 2, Shanton, 2.

Background/Purpose: Belimumab was approved for the treatment of non-renal SLE in 2011 and has been previously associated with a lower risk of damage progression when compared with prior 'usual care.' We sought to determine the risk of damage progression with belimumab versus alternative SLE immunosuppressants in a contemporary real world setting.

Methods: We identified all adults with SLE (defined by ≥2 ICD codes >30 days and < 2 years apart) in a United States multi-center electronic health record (EHR) database, TriNetX. We identified all patients who initiated belimumab, azathioprine (AZA), methotrexate (MTX), or mycophenolate (MMF) between 3/2011 and 8/2021. We designed and emulated a pragmatic target trial to compare the risk of damage progression with initiation of belimumab vs. AZA, belimumab vs. MTX, and belimumab vs MMF. For each comparison, eligible patients had never used the direct comparator but could have used other immunosuppressants and did not have lupus nephritis prior to the index date of treatment initiation. To emulate randomization, we used propensity score overlap weighting to balance baseline covariates, including demographics, geographic region, treatment initiation year, comorbidities including CKD, congestive heart failure, obesity, cardiovascular disease, the Charlson comorbidity index, tobacco use, SLE severity index (Garris C. J Med Econ 2013), SLE disease duration, baseline SLICC damage index score (categorized as 0, 1, or ≥2), medication use including glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, and other immunosuppressants, and healthcare utilization. We assessed the outcome of damage progression defined by an increase in the SLICC damage index (SDI), which was adapted to administrative data using ICD codes. We conducted an intention-to-treat analysis and a per-protocol analysis using pooled logistic regression where we adjusted for adherence to assigned treatment with inverse probability of treatment weighting. We also assessed the mean change in the SDI at three years among patients with ≥3 years of follow-up using linear regression.

Results: We compared 2,434 and 5,644 initiators of belimumab and AZA, (Table 1), 2,163 and 7,224 initiators of belimumab and MTX, and 2,431 and 6,350 initiators of belimumab and MMF, respectively. In each comparison, covariates were balanced after propensity score overlap weighting. 95% were female; the mean age was 44 years. 53% had a baseline SDI of zero. After 5 years, over 41% in each treatment group developed ≥1 new damage item on the SDI. The risk of damage progression was lower with belimumab than mycophenolate (HR 0.74 [95% CI 0.67-0.83]; Table 2), but there was no difference in the risk of damage progression between belimumab and AZA or belimumab and MTX. Similarly, belimumab was associated with a lower 3-year change in SDI when compared with MMF, but there was no difference when compared with AZA and MTX (Table 3).

Conclusion: In this real world EHR-based SLE cohort, after accounting for baseline covariates associated with the risk of organ damage, belimumab was associated with a lower risk of damage progression than MMF but not AZA or MTX use. Limitations include the use of administrative claims to identify components of the SDI.

.jpg)

A. Jorge: None; B. Zhou: None; Y. Zhang: None; H. Choi: Ani, 2, Horizon, 2, 5, LG, 2, Protalix, 2, Shanton, 2.