Poster Session A

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Session: (0582–0608) SLE – Treatment Poster I

0586: Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Azathioprine and Tacrolimus in SLE Pregnancies: Preliminary Results from the LEGACY Cohort

Sunday, November 12, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

- AM

Arielle Mendel, MD, FRCPC, MSc

McGill University Health Centre

Montréal, QC, CanadaDisclosure information not submitted.

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Reem Farhat1, Arielle Mendel2, Isabelle Malhamé3, Joo Young (Esther) Lee4, Luisa Ciofani5, Sasha Bernatsky6 and Evelyne Vinet2, 1McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2McGill University Health Centre, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5McGill University Health Center, Montreal, QC, Canada, 6Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada

Background/Purpose: Pregnant SLE women still face an unacceptably high risk of maternal and fetal morbidity, particularly when their disease is active. How to personalize SLE therapies to optimize pregnancy outcomes remains unknown. Though guidelines strongly recommend azathioprine (AZA) and tacrolimus (TAC) in specific SLE pregnancy scenarios, evidence to guide drug monitoring in this context is non-existent. Our aim is to evaluate the characteristics of SLE pregnancies according to the levels of AZA metabolites and TAC trough levels at the first pregnancy (baseline) visit.

Methods: LEGACY is a prospective cohort enrolling unselected SLE pregnancies ≤16 6/7 gestational weeks at 7 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics. We record demographics, disease activity, and drugs. In addition, whole blood samples are collected at baseline to determine AZA metabolites (e.g., erythrocyte-free 6-thioguanine, 6-TG) and trough TAC levels if applicable. The present study included Montreal LEGACY participants prescribed either AZA or TAC ≥3 months prior to their first pregnancy visit. We characterized AZA metabolite and TAC levels as continuous and categorical variables (i.e., non-adherent, sub-therapeutic, therapeutic, and supra-therapeutic, using established cut-offs in nonpregnant populations). We defined patients as non-adherent if they had undetectable or barely detectable levels despite appropriate dosing.

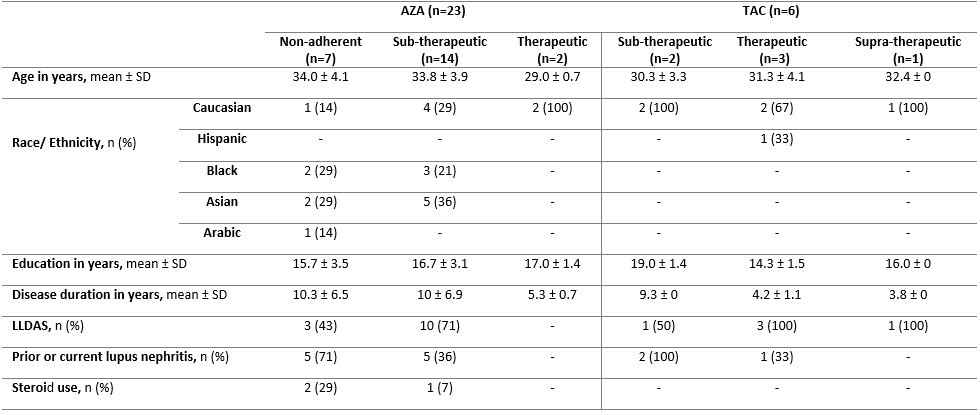

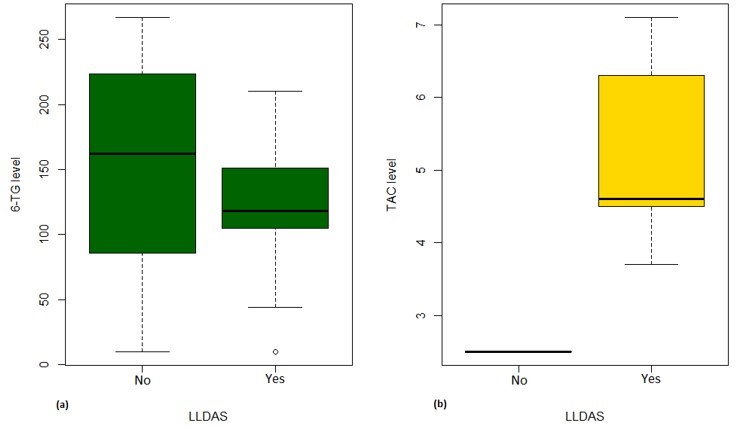

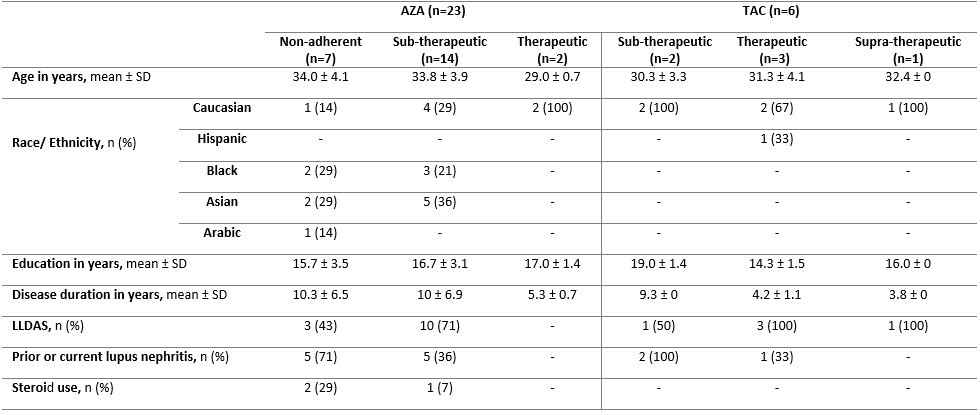

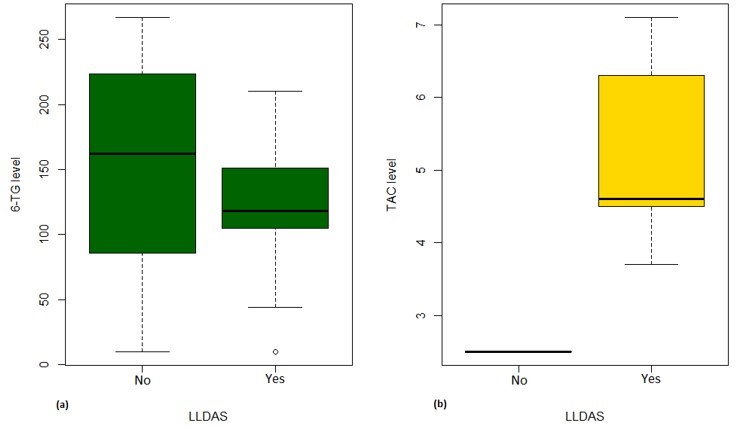

Results: Of 70 LEGACY pregnancies enrolled in Montreal, 23 (33%) and 6 (9%) were prescribed AZA and TAC, respectively. Among those prescribed AZA, only 9% had therapeutic levels, while 91% were subtherapeutic or non-adherent (Table 1). Compared to those with therapeutic levels, pregnancies with subtherapeutic or non-adherent AZA levels were more likely to occur in women of non-Caucasian ethnicity/race, on steroids, with longer SLE duration, and with prior lupus nephritis (Table 2). Among those prescribed TAC, 50% (3/6) had therapeutic levels, while 33% (2/6) and 17% (1/6) were subtherapeutic and supra-therapeutic, respectively. No patients on TAC were identified as non-adherent. Less than half (43%) of pregnancies non-adherent to AZA were in Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) at baseline. Of the pregnancies with sub-therapeutic TAC levels, 50% (1/2) were not in LLDAS, while all (4/4) pregnancies with therapeutic or supra-therapeutic TAC levels were in LLDAS at baseline.

Conclusion: We observed that most SLE pregnancies prescribed AZA had sub-therapeutic levels, with nearly a third identified as non-adherent. Pregnancies with lower AZA and TAC levels may be less likely to achieve LLDAS. Despite low numbers, our preliminary results suggest the value of personalized drug monitoring as a novel approach to precision medicine in pregnant SLE women, that might improve efficacy, safety, and adherence in a high-risk population.

.jpg)

R. Farhat: None; A. Mendel: None; I. Malhamé: None; J. Lee: None; L. Ciofani: None; S. Bernatsky: None; E. Vinet: None.

Background/Purpose: Pregnant SLE women still face an unacceptably high risk of maternal and fetal morbidity, particularly when their disease is active. How to personalize SLE therapies to optimize pregnancy outcomes remains unknown. Though guidelines strongly recommend azathioprine (AZA) and tacrolimus (TAC) in specific SLE pregnancy scenarios, evidence to guide drug monitoring in this context is non-existent. Our aim is to evaluate the characteristics of SLE pregnancies according to the levels of AZA metabolites and TAC trough levels at the first pregnancy (baseline) visit.

Methods: LEGACY is a prospective cohort enrolling unselected SLE pregnancies ≤16 6/7 gestational weeks at 7 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics. We record demographics, disease activity, and drugs. In addition, whole blood samples are collected at baseline to determine AZA metabolites (e.g., erythrocyte-free 6-thioguanine, 6-TG) and trough TAC levels if applicable. The present study included Montreal LEGACY participants prescribed either AZA or TAC ≥3 months prior to their first pregnancy visit. We characterized AZA metabolite and TAC levels as continuous and categorical variables (i.e., non-adherent, sub-therapeutic, therapeutic, and supra-therapeutic, using established cut-offs in nonpregnant populations). We defined patients as non-adherent if they had undetectable or barely detectable levels despite appropriate dosing.

Results: Of 70 LEGACY pregnancies enrolled in Montreal, 23 (33%) and 6 (9%) were prescribed AZA and TAC, respectively. Among those prescribed AZA, only 9% had therapeutic levels, while 91% were subtherapeutic or non-adherent (Table 1). Compared to those with therapeutic levels, pregnancies with subtherapeutic or non-adherent AZA levels were more likely to occur in women of non-Caucasian ethnicity/race, on steroids, with longer SLE duration, and with prior lupus nephritis (Table 2). Among those prescribed TAC, 50% (3/6) had therapeutic levels, while 33% (2/6) and 17% (1/6) were subtherapeutic and supra-therapeutic, respectively. No patients on TAC were identified as non-adherent. Less than half (43%) of pregnancies non-adherent to AZA were in Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) at baseline. Of the pregnancies with sub-therapeutic TAC levels, 50% (1/2) were not in LLDAS, while all (4/4) pregnancies with therapeutic or supra-therapeutic TAC levels were in LLDAS at baseline.

Conclusion: We observed that most SLE pregnancies prescribed AZA had sub-therapeutic levels, with nearly a third identified as non-adherent. Pregnancies with lower AZA and TAC levels may be less likely to achieve LLDAS. Despite low numbers, our preliminary results suggest the value of personalized drug monitoring as a novel approach to precision medicine in pregnant SLE women, that might improve efficacy, safety, and adherence in a high-risk population.

.jpg)

Table 1. Number of pregnancies and mean drug dose at baseline visit according to AZA metabolite (6-TG) and TAC trough levels

Table 2. Baseline maternal characteristics stratified according to AZA metabolite (6-TG) and TAC trough levels

Figure 1. Boxplot of 6-TG levels [pmol/8×108 RBC] (a) and TAC trough levels [ng/ml] (b) according to LLDAS

R. Farhat: None; A. Mendel: None; I. Malhamé: None; J. Lee: None; L. Ciofani: None; S. Bernatsky: None; E. Vinet: None.