Poster Session C

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) including psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

Session: (2227–2256) Spondyloarthritis Including Psoriatic Arthritis – Treatment Poster III: SpA

2239: Achievement of Disease Control in PsA Patients Treated with Upadacitinib at Week 152: Post Hoc Analysis of the Long-term Extensions of Two Phase 3 Trials

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Arthur Kavanaugh1, Kristi Mizelle2, Oliver FitzGerald3, Enrique Soriano4, Peter Nash5, Sandra Ciecinski6, Limei Zhou6, Arathi Setty6 and Laure Gossec7, 1Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, 2Tidewater Physicians Multispecialty Group, Newport News, VA, 3Conway Institute for Biomolecular Research, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 4Rheumatology Section, Internal Medicine Services, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, and University Institute Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 5School of Medicine, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia, 6AbbVie, Inc., North Chicago, IL, 7Sorbonne Université and Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France

Background/Purpose: A main goal of therapy for patients (pts) with PsA is to achieve and maintain the lowest possible level of disease activity across domains.1 Composite measures used to assess disease activity include Minimal Disease Activity (MDA)/Very Low Disease Activity (VLDA), as well as achievement of low disease activity (LDA) or remission (REM) using the Disease Activity index for PsA (DAPSA), PsA Disease Activity Score (PASDAS), and/or Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3). Here, we assess the achievement of goals according to these measures in pts with PsA following long-term treatment with upadacitinib (UPA), an oral JAK inhibitor, at week (wk) 152 from two phase 3 trials.

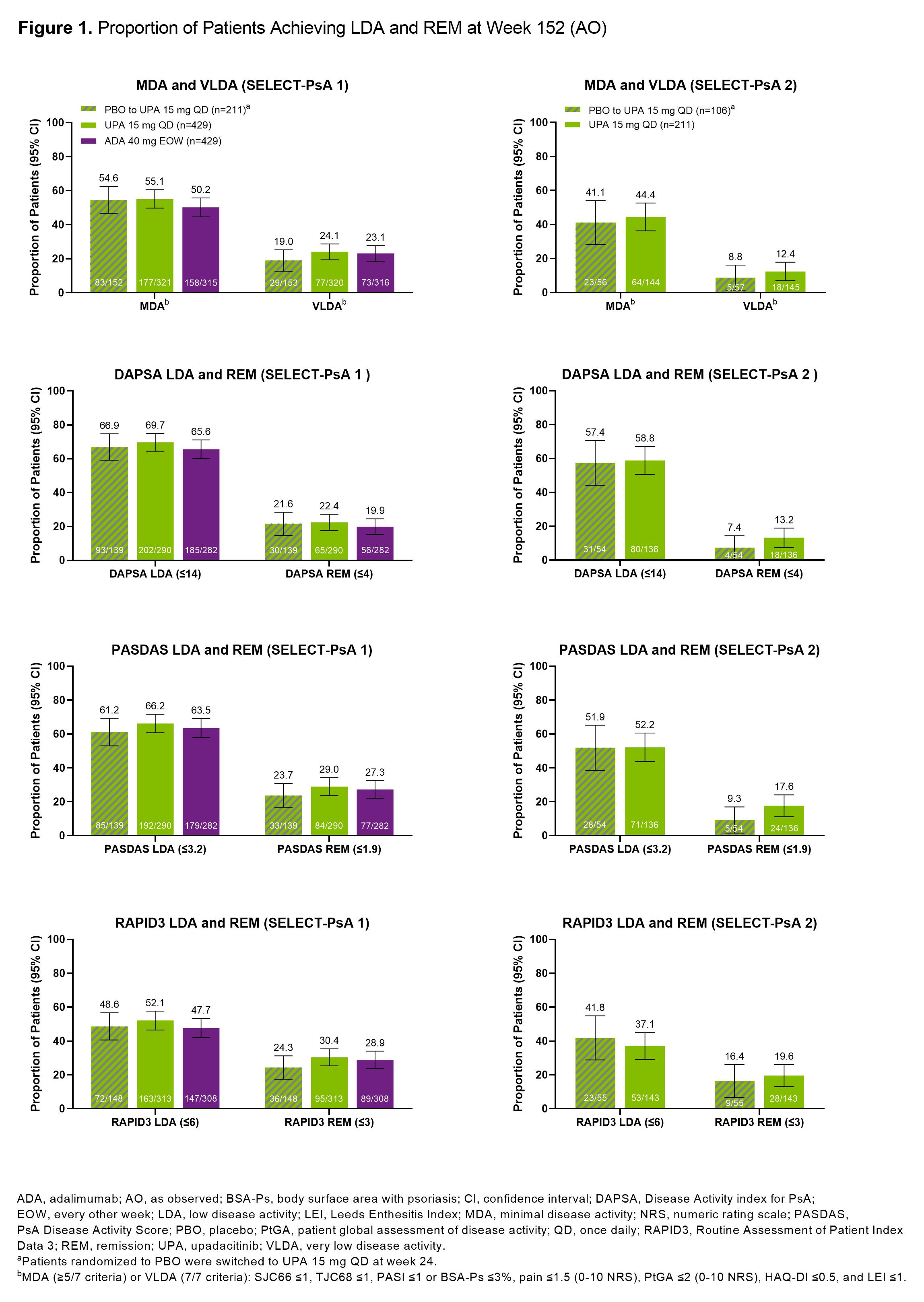

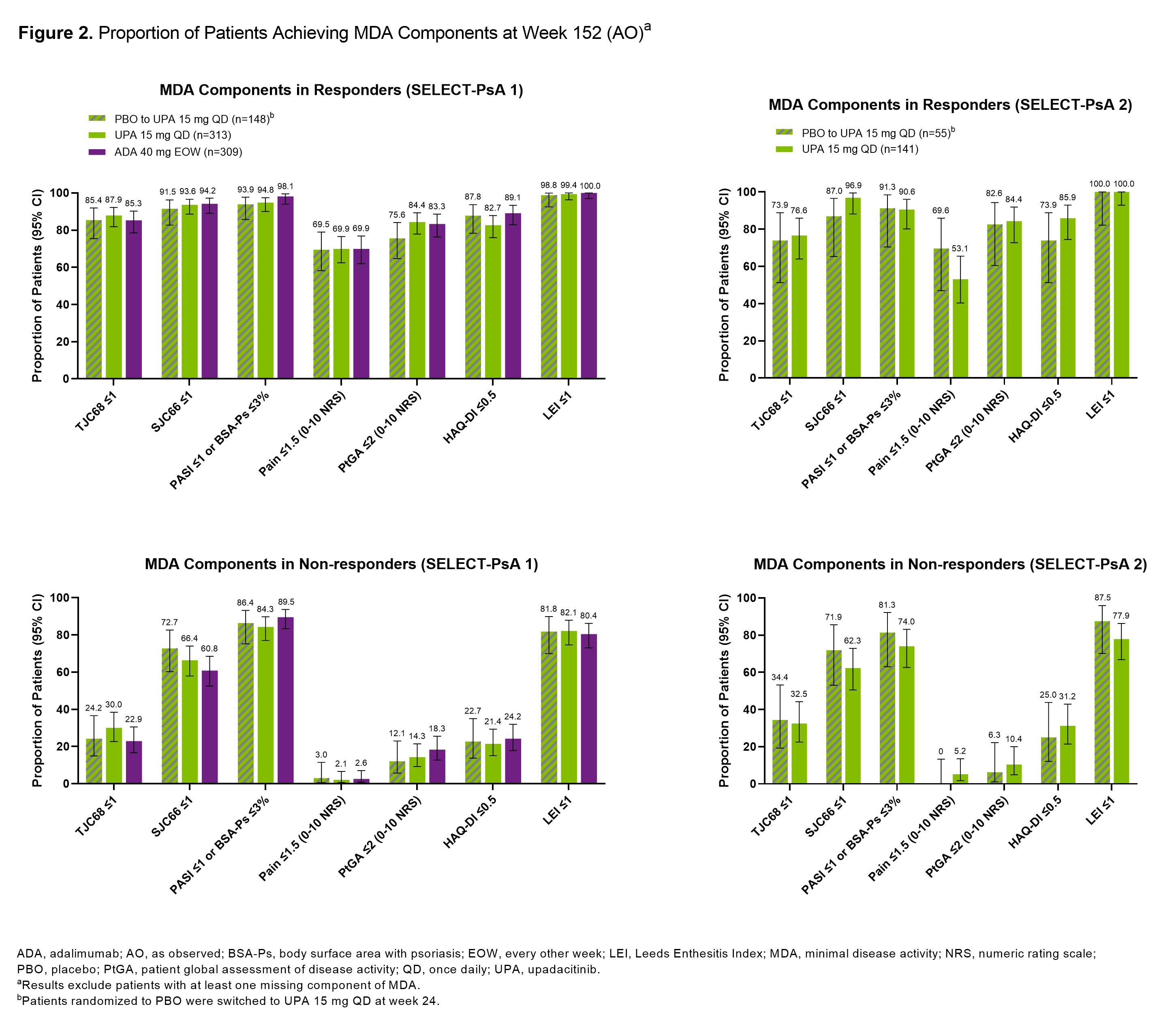

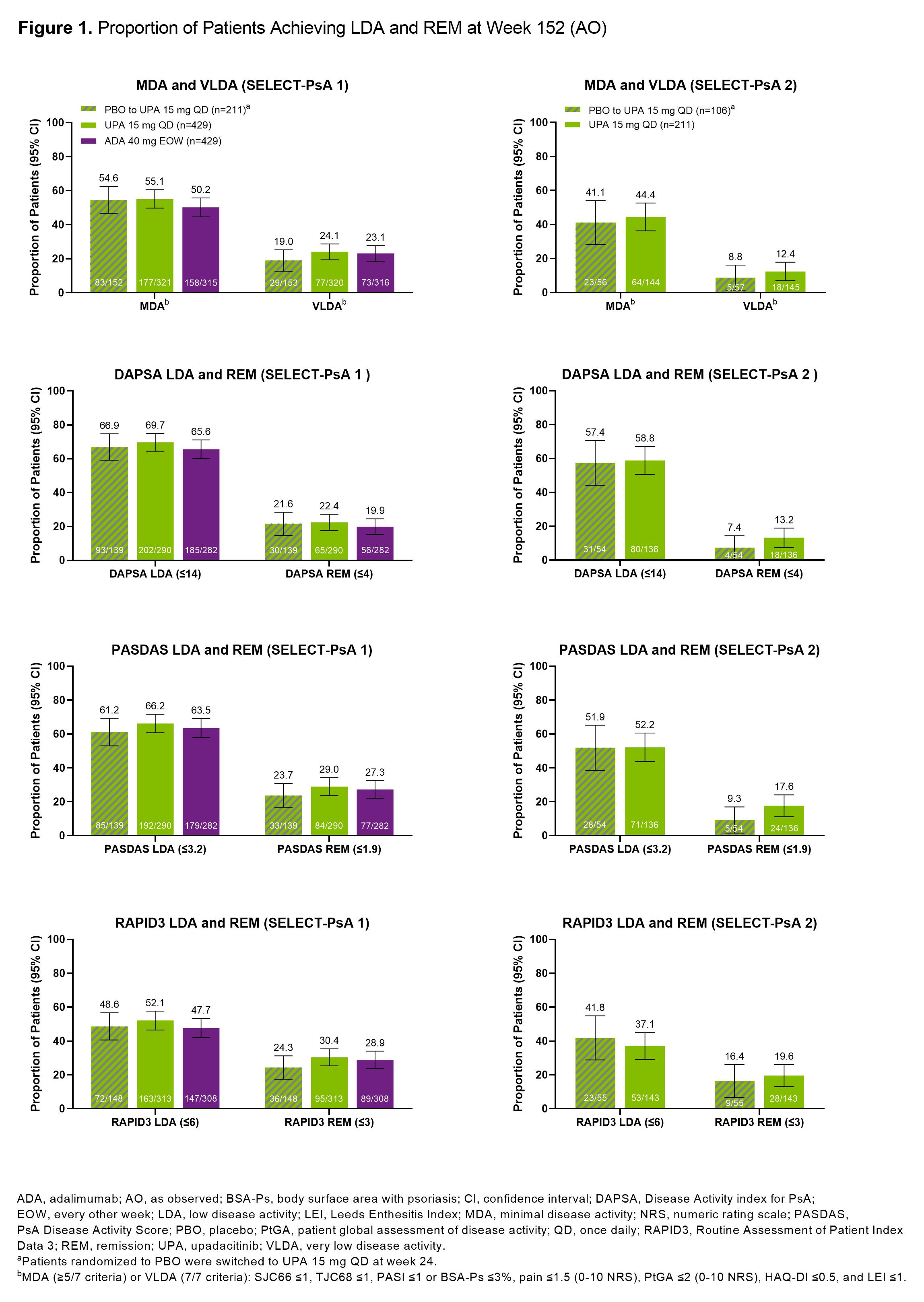

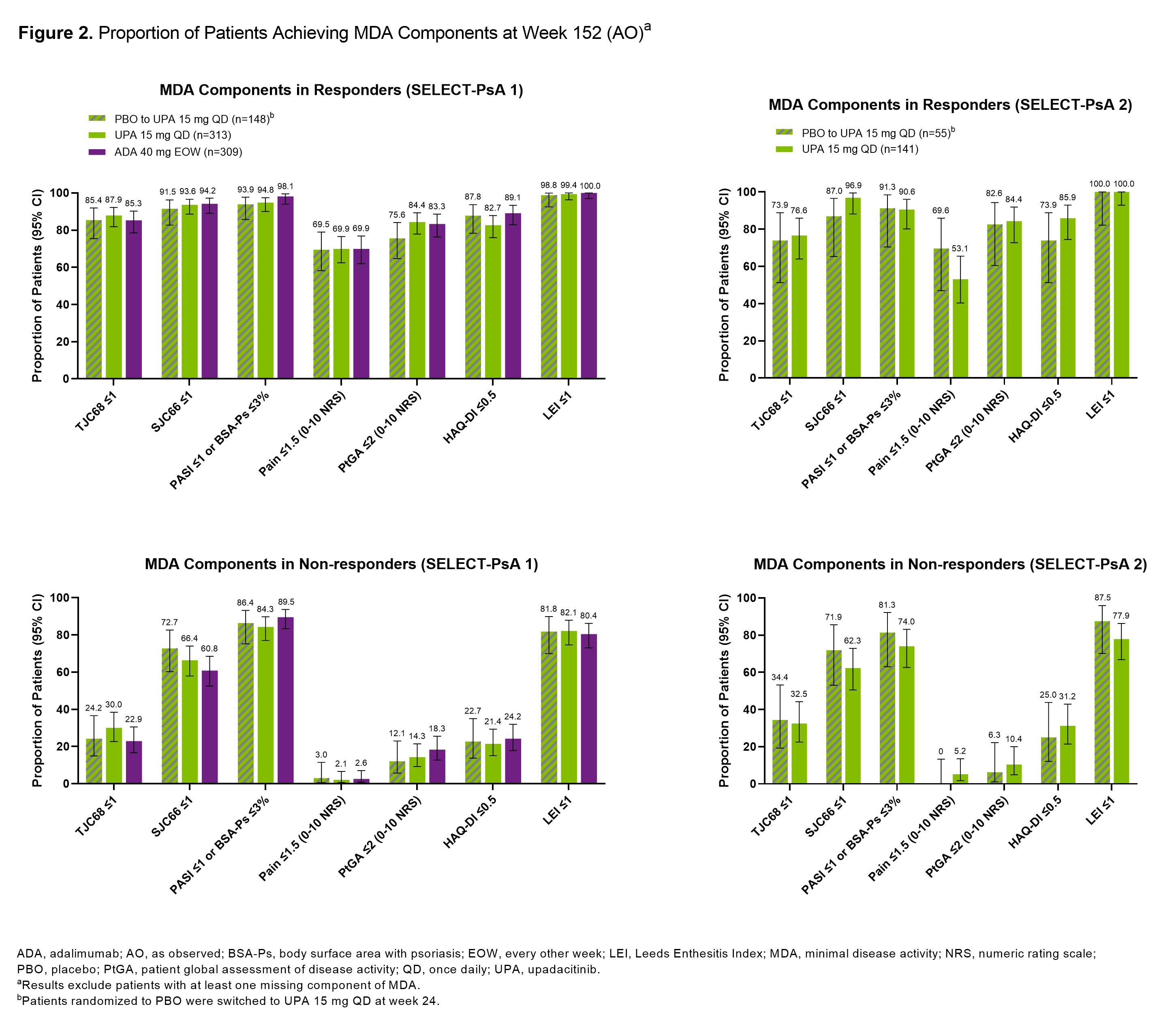

Methods: Post hoc analysis of pts from the SELECT-PsA 1 (N=1704; inadequate response to non-biologic DMARDs [non-bDMARD-IR]) and SELECT-PsA 2 (N=641; bDMARD-IR) studies was performed.2,3 Pts randomized to once daily UPA 15 mg (UPA15), placebo (switched to UPA15 at wk 24), or every other wk adalimumab (ADA; SELECT-PsA 1 study only) were evaluated. Proportions of pts achieving MDA (≥5/7 criteria)/VLDA (7/7 criteria), DAPSA LDA (≤14)/REM (≤4), PASDAS LDA (≤3.2)/REM (≤1.9), or RAPID3 LDA (≤6)/REM (≤3) at wk 152 were assessed. Additionally, proportions of pts achieving individual MDA components among those who did (responder) or did not (non-responder) achieve MDA at wk 152 are shown. As observed (AO) data are presented.

Results: At 3 years, ~50-70% of pts remained in the studies. In SELECT-PsA 1, similar proportions of pts treated with UPA15, PBO switched to UPA15, or ADA achieved MDA (range: 50-55%) or VLDA (range: 19-24%) at wk 152 (Figure 1). In SELECT-PsA 2, similar response rates were observed for MDA (range: 41-44%) and VLDA (range: 9-12%) amongst pts receiving UPA15 or PBO switched to UPA15. The proportions of pts achieving LDA or REM for DAPSA, PASDAS, and RAPID3 were similar between UPA15, PBO switched to UPA15, and ADA. As expected, pts identified as responders had higher response rates for all individual MDA components compared to non-responders across both studies (Figure 2). High proportions of responders and non-responders treated with UPA15 achieved SJC66 ≤1, PASI ≤1 or Body Surface Area-Psoriasis (BSA-Ps) ≤3%, and Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) ≤1; similar rates were observed with PBO switched to UPA15 and ADA. In contrast, TJC68 ≤1, pts assessment of pain ≤1.5, pts global assessment of disease activity ≤2, and HAQ-DI ≤0.5 appeared to be more difficult to achieve across all treatments.

Conclusion: Among pts who remained in the studies with data at wk 152, high rates of LDA and REM were reported in pts treated with UPA15, which were similar to PBO switched to UPA15 and ADA, across several measures of disease activity irrespective of prior DMARD exposure. Across measures of LDA and REM, response rates were numerically lower in SELECT-PsA 2, likely due to the treatment refractory population, compared to SELECT-PsA 1. Even in pts who did not achieve MDA at wk 152, treatment with UPA15 led to a high proportion of pts achieving SJC66 ≤1, PASI ≤1 or BSA-Ps ≤3%, and LEI ≤1 in both studies.

References:

1. Coates LC, et al. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18:465-79.

2. McKinnes IB, et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1227-39.

3. Mease PJ, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:312–320.

A. Kavanaugh: Amgen, 2, BMS, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, Novartis, 2, Pfizer, 2, UCB, 2; K. Mizelle: AbbVie/Abbott, 2, 6, Amgen, 6, Boehringer-Ingelheim, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 6, Janssen, 6, Pfizer, 6, UCB, 2; O. FitzGerald: AbbVie, 5, 6, Bristol Myers Squibb, 2, 5, Celgene, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, 5, Janssen, 2, 6, Novartis, 5, Pfizer Inc, 2, 5, 6; E. Soriano: AbbVie, 2, 5, 6, Amgen, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb, 6, Eli Lilly, 6, Janssen, 2, 5, 6, Novartis, 2, 5, 6, Pfizer, 5, 6, Roche, 2, 5, 6, UCB, 5, 6; P. Nash: AbbVie, 5, 6, Bristol Myers Squibb, 5, 6, Celgene, 5, 6, Eli Lilly, 5, 6, Galapagos, 5, 6, GSK, 5, 6, Janssen, 5, 6, Novartis, 5, 6, Pfizer Inc, 5, 6; S. Ciecinski: AbbVie, 3, 11; L. Zhou: AbbVie, 3, 11; A. Setty: AbbVie/Abbott, 3, 11; L. Gossec: AbbVie, 2, 12, Personal fees, Amgen, 2, Biogen, 5, BMS, 12, Personal fees, Celltrion, 12, Personal fees, Eli Lilly, 5, 12, Personal fees, Galapagos, 12, Personal fees, Janssen, 12, Personal fees, MSD, 12, Personal fees, Novartis, 5, 12, Personal fees, Pfizer, 12, Personal fees, Sandoz, 5, 12, Personal fees, UCB Pharma, 5, 12, Personal fees.

Background/Purpose: A main goal of therapy for patients (pts) with PsA is to achieve and maintain the lowest possible level of disease activity across domains.1 Composite measures used to assess disease activity include Minimal Disease Activity (MDA)/Very Low Disease Activity (VLDA), as well as achievement of low disease activity (LDA) or remission (REM) using the Disease Activity index for PsA (DAPSA), PsA Disease Activity Score (PASDAS), and/or Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3). Here, we assess the achievement of goals according to these measures in pts with PsA following long-term treatment with upadacitinib (UPA), an oral JAK inhibitor, at week (wk) 152 from two phase 3 trials.

Methods: Post hoc analysis of pts from the SELECT-PsA 1 (N=1704; inadequate response to non-biologic DMARDs [non-bDMARD-IR]) and SELECT-PsA 2 (N=641; bDMARD-IR) studies was performed.2,3 Pts randomized to once daily UPA 15 mg (UPA15), placebo (switched to UPA15 at wk 24), or every other wk adalimumab (ADA; SELECT-PsA 1 study only) were evaluated. Proportions of pts achieving MDA (≥5/7 criteria)/VLDA (7/7 criteria), DAPSA LDA (≤14)/REM (≤4), PASDAS LDA (≤3.2)/REM (≤1.9), or RAPID3 LDA (≤6)/REM (≤3) at wk 152 were assessed. Additionally, proportions of pts achieving individual MDA components among those who did (responder) or did not (non-responder) achieve MDA at wk 152 are shown. As observed (AO) data are presented.

Results: At 3 years, ~50-70% of pts remained in the studies. In SELECT-PsA 1, similar proportions of pts treated with UPA15, PBO switched to UPA15, or ADA achieved MDA (range: 50-55%) or VLDA (range: 19-24%) at wk 152 (Figure 1). In SELECT-PsA 2, similar response rates were observed for MDA (range: 41-44%) and VLDA (range: 9-12%) amongst pts receiving UPA15 or PBO switched to UPA15. The proportions of pts achieving LDA or REM for DAPSA, PASDAS, and RAPID3 were similar between UPA15, PBO switched to UPA15, and ADA. As expected, pts identified as responders had higher response rates for all individual MDA components compared to non-responders across both studies (Figure 2). High proportions of responders and non-responders treated with UPA15 achieved SJC66 ≤1, PASI ≤1 or Body Surface Area-Psoriasis (BSA-Ps) ≤3%, and Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI) ≤1; similar rates were observed with PBO switched to UPA15 and ADA. In contrast, TJC68 ≤1, pts assessment of pain ≤1.5, pts global assessment of disease activity ≤2, and HAQ-DI ≤0.5 appeared to be more difficult to achieve across all treatments.

Conclusion: Among pts who remained in the studies with data at wk 152, high rates of LDA and REM were reported in pts treated with UPA15, which were similar to PBO switched to UPA15 and ADA, across several measures of disease activity irrespective of prior DMARD exposure. Across measures of LDA and REM, response rates were numerically lower in SELECT-PsA 2, likely due to the treatment refractory population, compared to SELECT-PsA 1. Even in pts who did not achieve MDA at wk 152, treatment with UPA15 led to a high proportion of pts achieving SJC66 ≤1, PASI ≤1 or BSA-Ps ≤3%, and LEI ≤1 in both studies.

References:

1. Coates LC, et al. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18:465-79.

2. McKinnes IB, et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1227-39.

3. Mease PJ, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:312–320.

A. Kavanaugh: Amgen, 2, BMS, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, Novartis, 2, Pfizer, 2, UCB, 2; K. Mizelle: AbbVie/Abbott, 2, 6, Amgen, 6, Boehringer-Ingelheim, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 6, Janssen, 6, Pfizer, 6, UCB, 2; O. FitzGerald: AbbVie, 5, 6, Bristol Myers Squibb, 2, 5, Celgene, 2, Eli Lilly, 2, 5, Janssen, 2, 6, Novartis, 5, Pfizer Inc, 2, 5, 6; E. Soriano: AbbVie, 2, 5, 6, Amgen, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb, 6, Eli Lilly, 6, Janssen, 2, 5, 6, Novartis, 2, 5, 6, Pfizer, 5, 6, Roche, 2, 5, 6, UCB, 5, 6; P. Nash: AbbVie, 5, 6, Bristol Myers Squibb, 5, 6, Celgene, 5, 6, Eli Lilly, 5, 6, Galapagos, 5, 6, GSK, 5, 6, Janssen, 5, 6, Novartis, 5, 6, Pfizer Inc, 5, 6; S. Ciecinski: AbbVie, 3, 11; L. Zhou: AbbVie, 3, 11; A. Setty: AbbVie/Abbott, 3, 11; L. Gossec: AbbVie, 2, 12, Personal fees, Amgen, 2, Biogen, 5, BMS, 12, Personal fees, Celltrion, 12, Personal fees, Eli Lilly, 5, 12, Personal fees, Galapagos, 12, Personal fees, Janssen, 12, Personal fees, MSD, 12, Personal fees, Novartis, 5, 12, Personal fees, Pfizer, 12, Personal fees, Sandoz, 5, 12, Personal fees, UCB Pharma, 5, 12, Personal fees.