Poster Session C

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Session: (2257–2325) SLE – Diagnosis, Manifestations, & Outcomes Poster III

2263: Disease Activity Progression in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Analysis of the SLE Prospective Observational Cohort Study (SPOCS)

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

.png)

Eric Morand, MD, PhD

Monash University

Clayton, Victoria, AustraliaDisclosure information not submitted.

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Eric Morand1, Richard Furie2, Christine Peschken3, Martin Aringer4, Laurent Arnaud5, Barnabas Desta6, Tina Grünfeld Eén7, Alessandro Sorrentino8, Stephanie Chen9 and Bo Ding7, 1Monash University, Centre for Inflammatory Diseases, Melbourne, Australia, 2Northwell Health, Manhasset, NY, 3University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 4Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden, Germany, 5University Hospitals of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France, 6BioPharmaceuticals R&D, AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, MD, 7BioPharmaceuticals Medical, AstraZeneca, Gothenburg, Sweden, 8Medical Affairs, AstraZeneca, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 9BioPharmaceuticals Medical, AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, MD

Background/Purpose: The international, multicenter SLE Prospective Observational Cohort Study (SPOCS) collected data on patients with SLE in relation to their type 1 interferon gene signature (IFNGS) status. Here, we report SLE disease activity progression over time—overall and by IFNGS category.

Methods: Eligible patients (aged ≥18 years) had physician-confirmed SLE (ACR or SLICC classification), ≥1 lifetime positive serology of ANA or dsDNA, a ≥6-month treatment duration with systemic SLE treatment beyond non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics, and moderate-to-severe activity at enrollment. Disease activity was assessed by the modified Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K), as well as by instances of flares, the Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS), and remission according to the 2021 Definition of Remission In Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (DORIS). IFNGS tests were conducted in a central laboratory; each sample was compared to pre-established cutoffs and given a qualitative diagnostic score, denoting low or high IFNGS. Comparisons between low and high IFNGS categories were performed with the chi-square test.

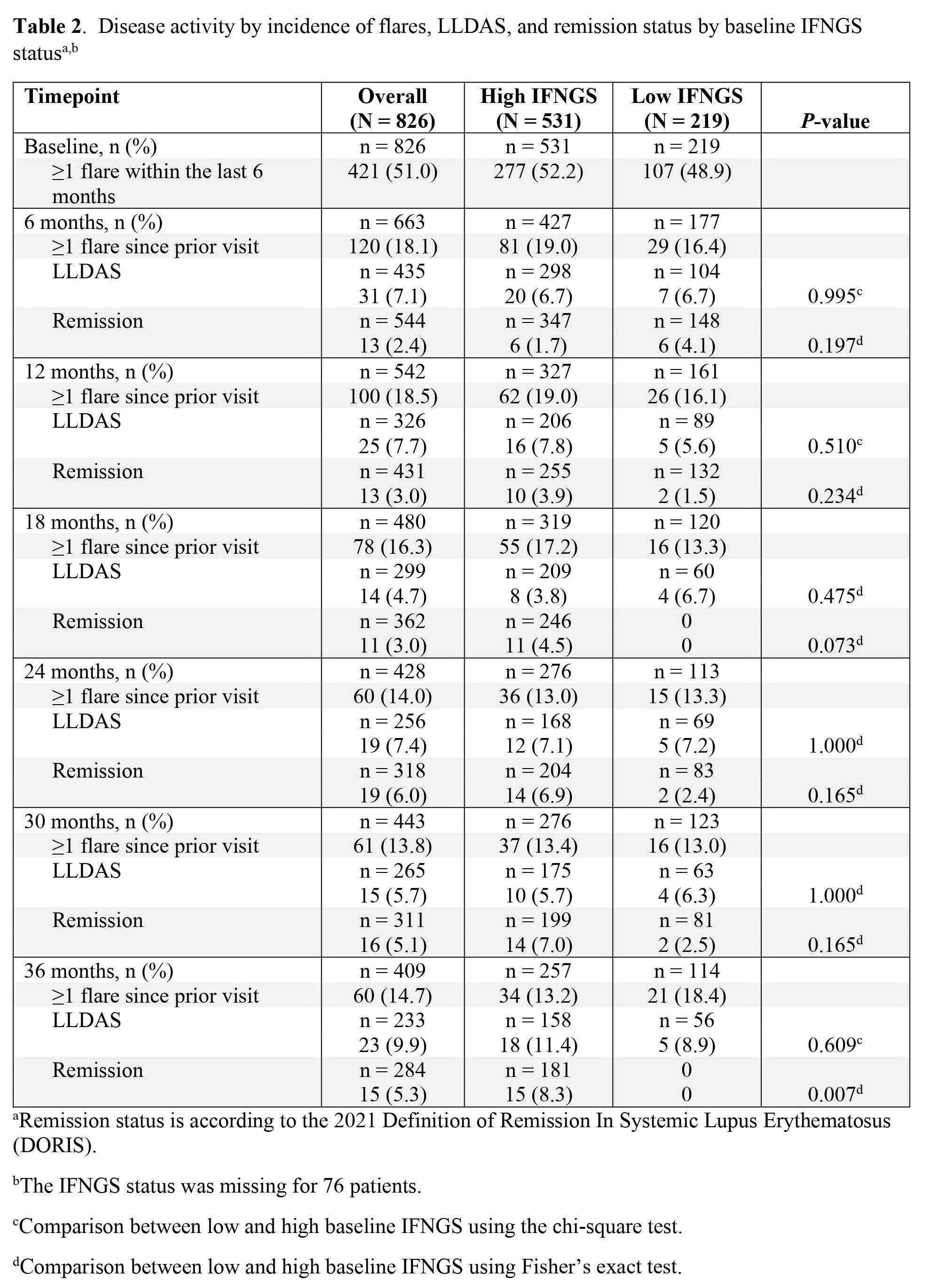

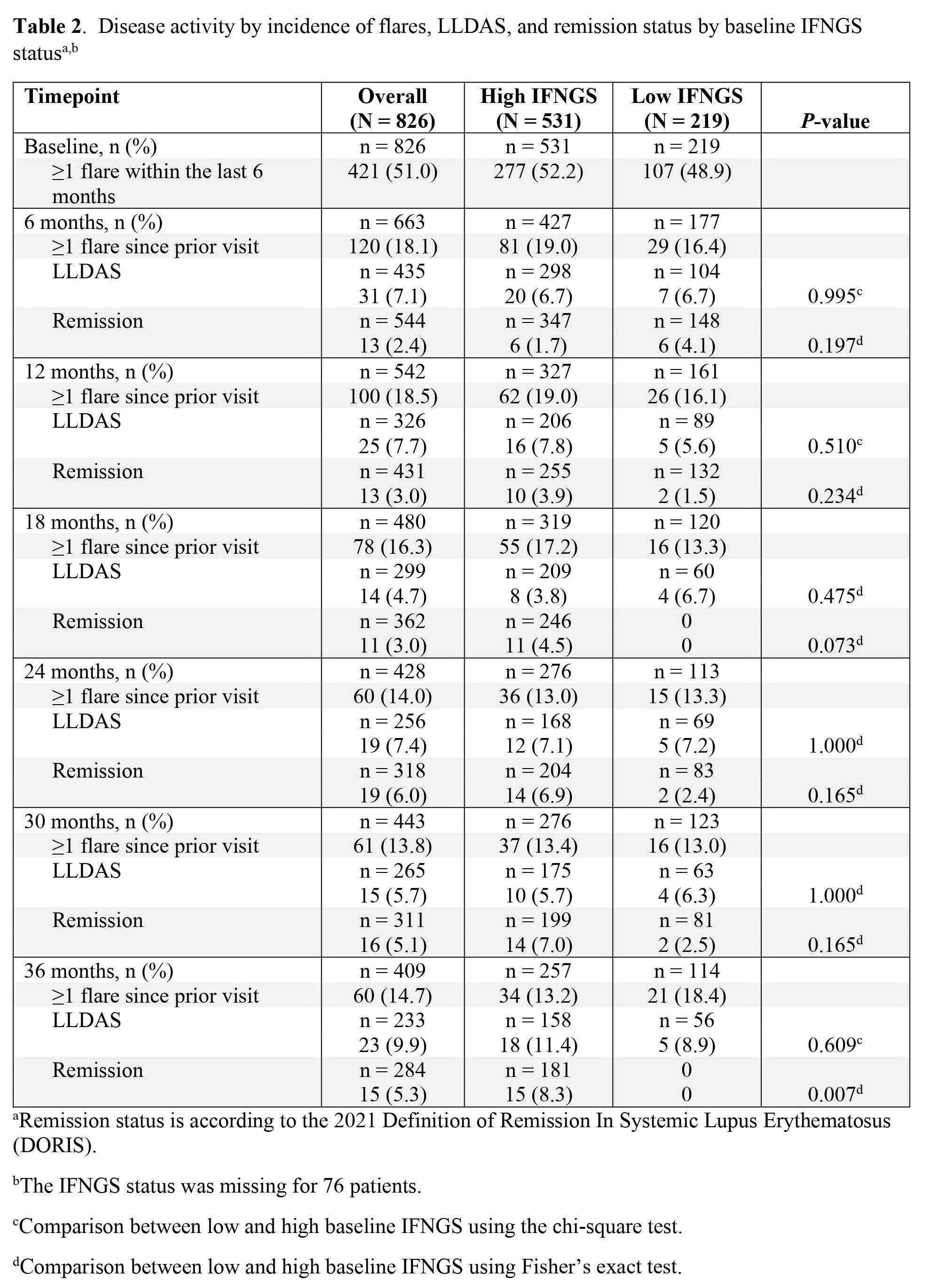

Results: A total of 826 patients were enrolled; 70.8% (n = 531) and 29.2% (n = 219) of patients had high and low baseline IFNGS, respectively, and the IFNGS status was missing for 76 patients. At baseline, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) SLEDAI-2K was 9.8 (4.6; n = 591); 58.2% (n = 344) of patients had a score of < 10. The mean (SD) SLEDAI-2K total scores at baseline were slightly lower in patients with a low IFNGS (9.2 [5.2]) compared with those with a high IFNGS (9.8 [4.3]; Table 1). Furthermore, a greater percentage of patients with a low IFNGS had SLEDAI-2K total scores of < 10 compared to those with a high IFNGS (66.4% [n = 91] vs 57.2% [n = 227], respectively). At baseline, 51.0% (n = 421) of patients reported having had ≥1 flare within the last 6 months; these were reported in similar percentages of patients with high and low IFNGS (52.2% [n = 277] vs 48.9% [n = 107], respectively; Table 2). Across the first 6 months, the percentage of patients reporting ≥1 flare since baseline was 18.1% (n = 120; high IFNGS, 19.0% [n = 81]; low IFNGS, 16.4% [n = 29]). At 6 months, the same percentage of patients with low IFNGS and high IFNGS achieved LLDAS (6.7% [n = 7] and 6.7% [n = 20], respectively), but a numerically higher percentage of patients with low IFNGS versus high IFNGS achieved remission (4.1% [n = 6] vs 1.7% [n = 6], respectively). The mean SLEDAI-2K total scores and percentages of patients reporting new flares changed little after 6 months, regardless of the baseline IFNGS status. Less than 10% of patients achieved LLDAS and less than 10% achieved remission during the entire 36 months of follow-up.

Conclusion: Although flare rates observed prospectively were lower than those reported by patients at enrollment, patients continued to have flares over the course of 36 months. There was no significant improvement in disease activity, and there were low rates of LLDAS and remission. Altogether, these indicate an unmet need for improved treatment outcomes.

.jpg)

E. Morand: AbbVie, 2, 5, Amgen, 5, AstraZeneca, 2, 5, 6, Biogen, 2, 5, Bristol Myers Squibb, 2, 5, Eli Lilly, 2, 5, EMD Serono, 2, 5, Galapagos, 2, Genentech, 2, 5, GlaxoSmithKline, 2, 5, IgM, 2, Janssen, 2, 5, Novartis, 2, Servier, 2, Takeda, 2, UCB, 5; R. Furie: Biogen, 2, 5; C. Peschken: AstraZeneca, 2, 5, GSK, 2, 5, Roche, 1, 2; M. Aringer: AbbVie/Abbott, 1, 6, Boehringer-Ingelheim, 1, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 1, 6, Chugai Pharma, 6, Eli Lilly, 1, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 1, 6, Merck/MSD, 6, Novartis, 1, Otsuka Pharma, 1, 6, Pfizer, 1, 6, Roche, 1, 6, Sanofi Aventis, 1, 6, UCB, 1, 6; L. Arnaud: AbbVie, 6, Alexion, 6, Alpine, 2, 6, Amgen, 6, AstraZeneca, 1, 2, 6, Biogen, 6, Boehringer Ingelheim, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 2, 6, Eli Lilly, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 1, 2, 6, Grifols, 6, Janssen, 6, Kezar Life Sciences, 2, 6, LFB, 6, Medac, 6, Novartis, 2, 6, Pfizer, 6, Roche-Chugaï, 6, UCB, 6; B. Desta: AstraZeneca, 3; T. Grünfeld Eén: AstraZeneca, 3, 11; A. Sorrentino: AbbVie/Abbott, 12, Own stocks, AstraZeneca, 3, Galapagos, 12, Own stocks, Gilead, 12, Own stocks, Moderna, 12, Own stocks; S. Chen: AstraZeneca, 3, 11; B. Ding: AstraZeneca, 3.

Background/Purpose: The international, multicenter SLE Prospective Observational Cohort Study (SPOCS) collected data on patients with SLE in relation to their type 1 interferon gene signature (IFNGS) status. Here, we report SLE disease activity progression over time—overall and by IFNGS category.

Methods: Eligible patients (aged ≥18 years) had physician-confirmed SLE (ACR or SLICC classification), ≥1 lifetime positive serology of ANA or dsDNA, a ≥6-month treatment duration with systemic SLE treatment beyond non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics, and moderate-to-severe activity at enrollment. Disease activity was assessed by the modified Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K), as well as by instances of flares, the Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS), and remission according to the 2021 Definition of Remission In Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (DORIS). IFNGS tests were conducted in a central laboratory; each sample was compared to pre-established cutoffs and given a qualitative diagnostic score, denoting low or high IFNGS. Comparisons between low and high IFNGS categories were performed with the chi-square test.

Results: A total of 826 patients were enrolled; 70.8% (n = 531) and 29.2% (n = 219) of patients had high and low baseline IFNGS, respectively, and the IFNGS status was missing for 76 patients. At baseline, the mean (standard deviation [SD]) SLEDAI-2K was 9.8 (4.6; n = 591); 58.2% (n = 344) of patients had a score of < 10. The mean (SD) SLEDAI-2K total scores at baseline were slightly lower in patients with a low IFNGS (9.2 [5.2]) compared with those with a high IFNGS (9.8 [4.3]; Table 1). Furthermore, a greater percentage of patients with a low IFNGS had SLEDAI-2K total scores of < 10 compared to those with a high IFNGS (66.4% [n = 91] vs 57.2% [n = 227], respectively). At baseline, 51.0% (n = 421) of patients reported having had ≥1 flare within the last 6 months; these were reported in similar percentages of patients with high and low IFNGS (52.2% [n = 277] vs 48.9% [n = 107], respectively; Table 2). Across the first 6 months, the percentage of patients reporting ≥1 flare since baseline was 18.1% (n = 120; high IFNGS, 19.0% [n = 81]; low IFNGS, 16.4% [n = 29]). At 6 months, the same percentage of patients with low IFNGS and high IFNGS achieved LLDAS (6.7% [n = 7] and 6.7% [n = 20], respectively), but a numerically higher percentage of patients with low IFNGS versus high IFNGS achieved remission (4.1% [n = 6] vs 1.7% [n = 6], respectively). The mean SLEDAI-2K total scores and percentages of patients reporting new flares changed little after 6 months, regardless of the baseline IFNGS status. Less than 10% of patients achieved LLDAS and less than 10% achieved remission during the entire 36 months of follow-up.

Conclusion: Although flare rates observed prospectively were lower than those reported by patients at enrollment, patients continued to have flares over the course of 36 months. There was no significant improvement in disease activity, and there were low rates of LLDAS and remission. Altogether, these indicate an unmet need for improved treatment outcomes.

.jpg)

Table 1

Table 2

E. Morand: AbbVie, 2, 5, Amgen, 5, AstraZeneca, 2, 5, 6, Biogen, 2, 5, Bristol Myers Squibb, 2, 5, Eli Lilly, 2, 5, EMD Serono, 2, 5, Galapagos, 2, Genentech, 2, 5, GlaxoSmithKline, 2, 5, IgM, 2, Janssen, 2, 5, Novartis, 2, Servier, 2, Takeda, 2, UCB, 5; R. Furie: Biogen, 2, 5; C. Peschken: AstraZeneca, 2, 5, GSK, 2, 5, Roche, 1, 2; M. Aringer: AbbVie/Abbott, 1, 6, Boehringer-Ingelheim, 1, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 1, 6, Chugai Pharma, 6, Eli Lilly, 1, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 1, 6, Merck/MSD, 6, Novartis, 1, Otsuka Pharma, 1, 6, Pfizer, 1, 6, Roche, 1, 6, Sanofi Aventis, 1, 6, UCB, 1, 6; L. Arnaud: AbbVie, 6, Alexion, 6, Alpine, 2, 6, Amgen, 6, AstraZeneca, 1, 2, 6, Biogen, 6, Boehringer Ingelheim, 6, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), 2, 6, Eli Lilly, 6, GlaxoSmithKlein(GSK), 1, 2, 6, Grifols, 6, Janssen, 6, Kezar Life Sciences, 2, 6, LFB, 6, Medac, 6, Novartis, 2, 6, Pfizer, 6, Roche-Chugaï, 6, UCB, 6; B. Desta: AstraZeneca, 3; T. Grünfeld Eén: AstraZeneca, 3, 11; A. Sorrentino: AbbVie/Abbott, 12, Own stocks, AstraZeneca, 3, Galapagos, 12, Own stocks, Gilead, 12, Own stocks, Moderna, 12, Own stocks; S. Chen: AstraZeneca, 3, 11; B. Ding: AstraZeneca, 3.