Poster Session A

Diversity, inclusion and racial disparities

Session: (0176–0195) Healthcare Disparities in Rheumatology Poster I: Lupus

0180: Multiplicative Impact of Adverse Social Determinants of Health on Outcomes in Lupus Nephritis: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review

Sunday, November 12, 2023

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM PT

Location: Poster Hall

- SG

Shivani Garg, MD, MS

University of Madison, School of Medicine and Public Health

Madison, WI, United StatesDisclosure(s): No financial relationships with ineligible companies to disclose

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Shivani Garg1, Brianna Boderman2, Nadia Sweet2, Daniel Montes3, Brad Astor2, S. Sam Lim4 and Christie M. Bartels2, 1Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, 2University of Wisconsin, School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, 3Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, 4Emory University, Atlanta, GA

Background/Purpose: Lupus results in 58% more organ damage in people of Black race in the US compared to African descendants living in 11 other developed countries. This highlights that social determinants of health (SDH) likely contribute to disparities in LN outcomes in the US. However, the overall burden of adverse SDHs on LN outcomes and how each SDH domain contributes to observed health disparities have not been fully examined. In the absence of such information, health disparities between racial/ethnic groups may be interpreted as inherently "biological" or "cultural" differences. Thus, there is a need to understand the underlying mechanisms explaining how SDHs influence outcomes and contribute to health disparities in LN to advance equity. Objectives of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to: 1) determine the odds of poor LN outcomes in patients with i) any adverse SDHs, and ii) specific SDH domains; 2) develop a framework for the multidimensional impact of SDH on LN outcomes.

Methods: A comprehensive search was performed using MeSH headings and keywords (e.g., lupus nephritis, insurance, poverty, neighborhood socio-economic status, death, etc.) in Medline, Embase, CINAHL and Web of Science. We included observational and interventional studies on human subjects measuring associations between SDHs and LN outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using standard tools for all studies.

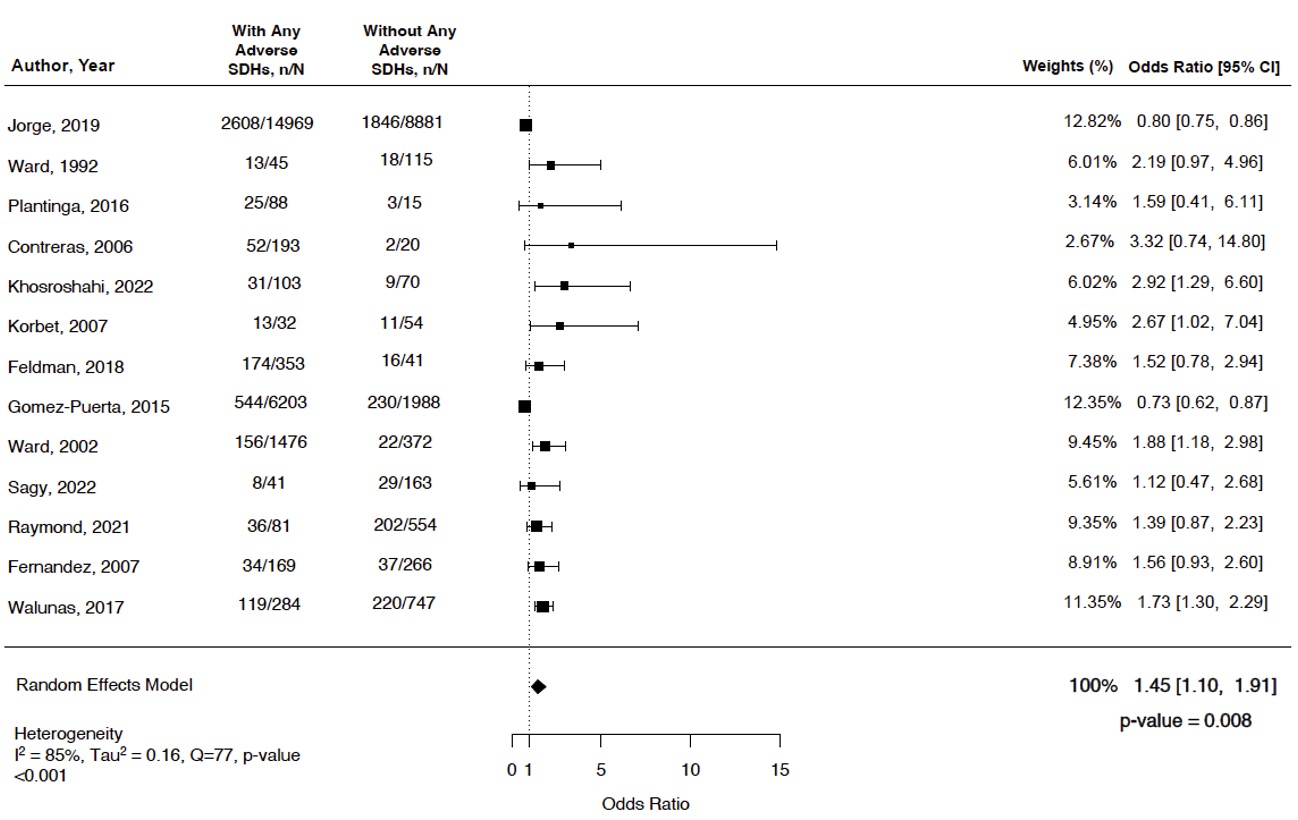

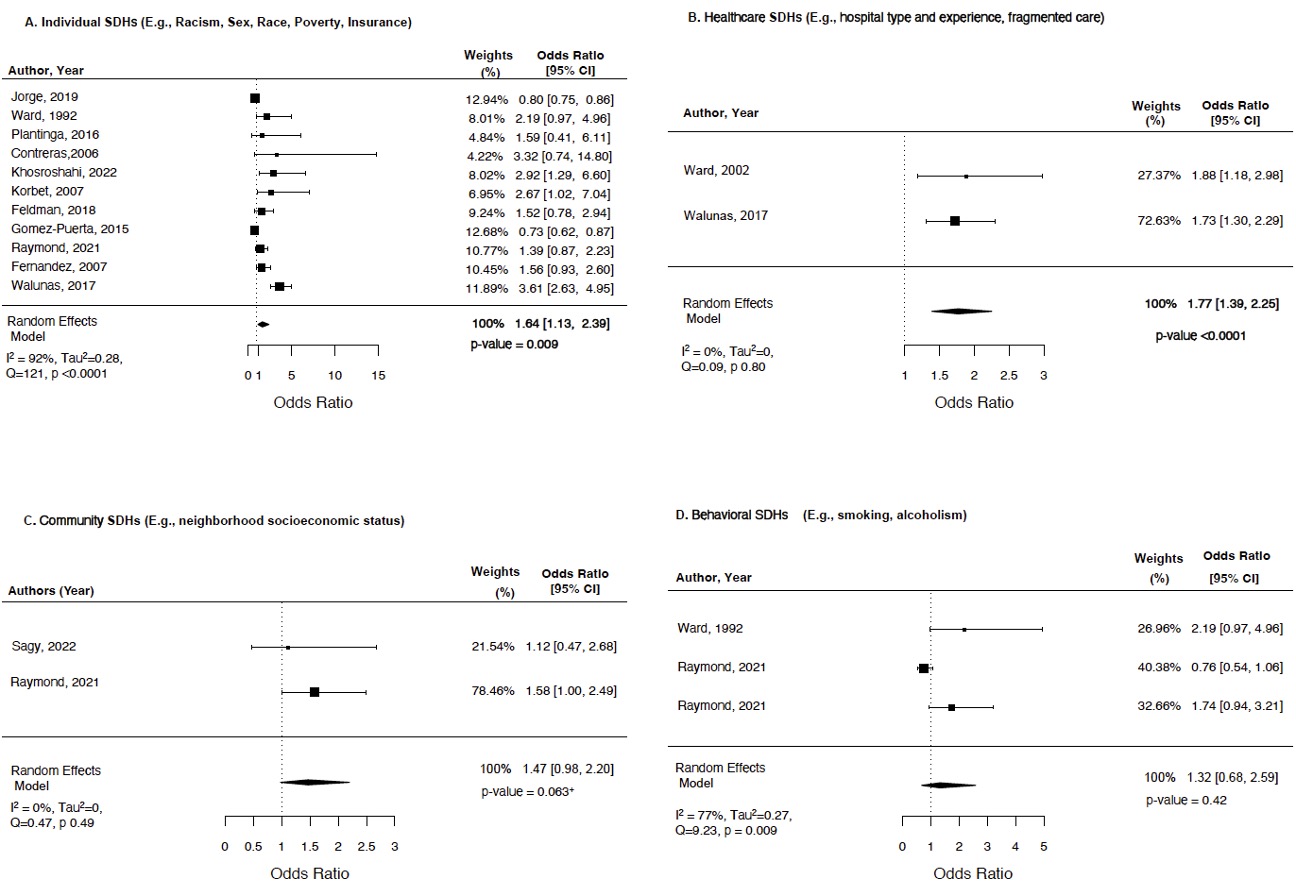

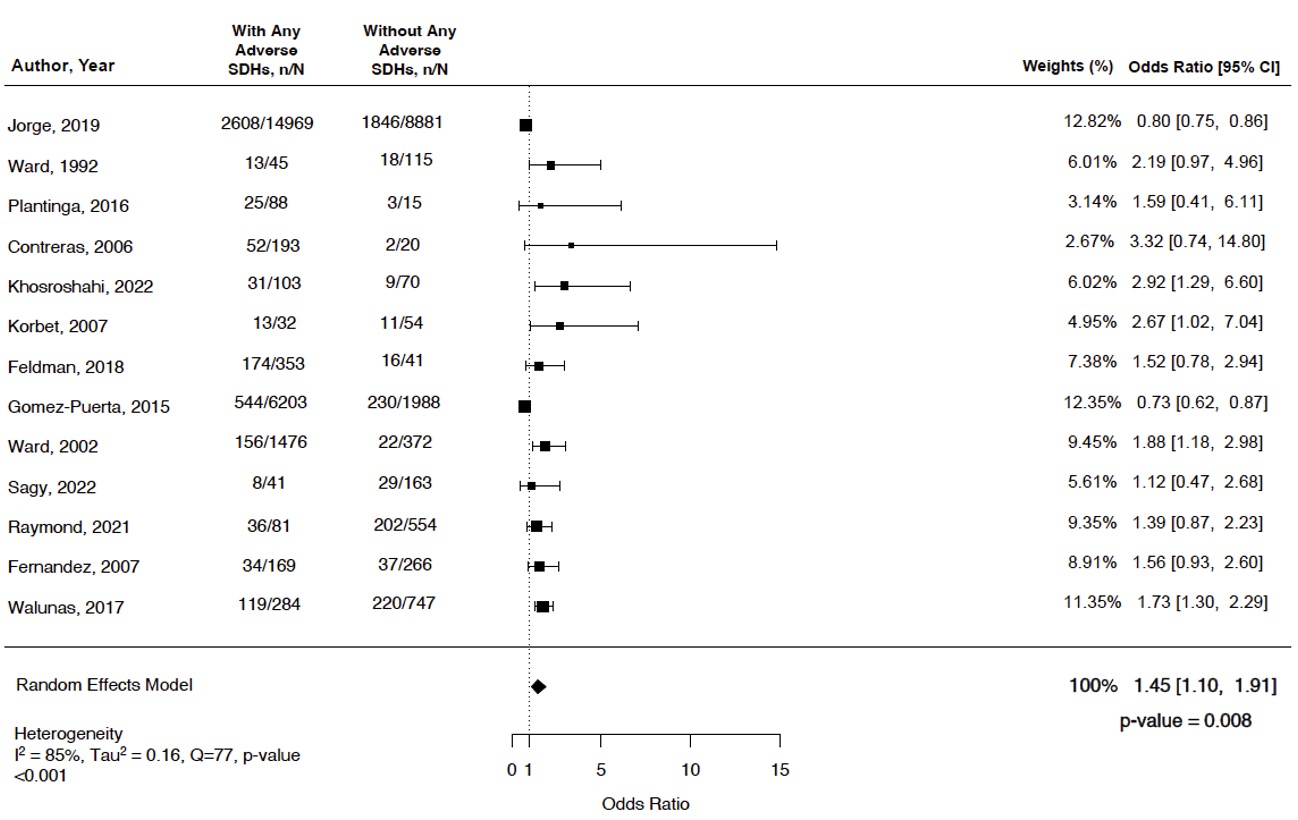

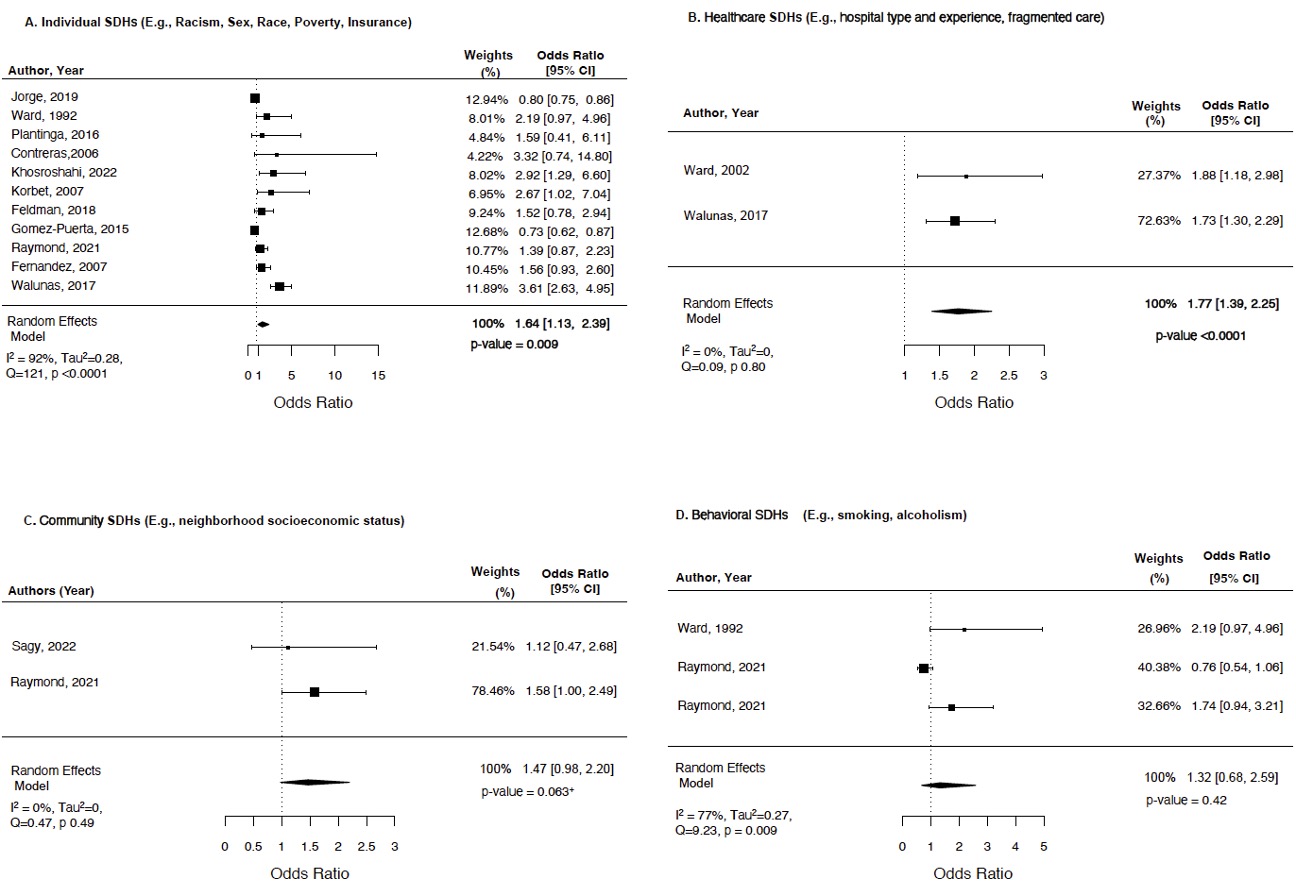

We examined pooled odds of severe LN outcomes (primary outcome) including mortality, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), or cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with and without any adverse SDHs using a random effects model. Additionally, we calculated the pooled odds of poor outcomes by each SDH domain: individual (e.g., race, insurance), healthcare (e.g., fragmented care, hospital experience), community (e.g., neighborhood socioeconomic status), and behavioral (e.g., smoking) (Fig. 1). Heterogeneity was assessed using I2.

Results: Among 531 manually reviewed abstracts, 31 met inclusion. Only 13 studies comparing LN outcomes in patients with and without adverse SDHs were included in the meta-analysis. Overall 92% of studies had low risk of bias. The pooled odds of poor outcomes (death, ESKD, or CVD) in patients with any adverse SDHs were 45% higher compared to those without any adverse SDHs (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.10-1.91, p = 0.008, I2 85%, Fig. 2). Among the four SDH domains, 64% and 77% higher odds of poor outcomes were noted in patients with adverse SDHs in individual and healthcare domains (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.13-2.39, I2 92%; OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.2-3.0, I2 0%; Fig. 3A-D). Our framework highlighted a multiplicative impact of adverse SDHs in different domains on poor LN outcomes (Fig. 1). As illustrated in Fig. 1, patients of Black race with fragmented care and public insurance had 12-fold higher odds of mortality/ESKD.

Conclusion: Our study reports a strong negative impact of adverse SDHs on LN outcomes, with the worst impact in patients with adverse individual and healthcare SDH domains. Moreover, having adverse SDHs in ≥2 domains had a multiplicative impact leading to 12-fold higher odds of poor outcomes, widening health disparities in LN. These findings could guide future health-equity focused interventions to address outcome disparities in LN.

.jpg)

S. Garg: None; B. Boderman: None; N. Sweet: None; D. Montes: None; B. Astor: None; S. Lim: None; C. Bartels: Pfizer, 5.

Background/Purpose: Lupus results in 58% more organ damage in people of Black race in the US compared to African descendants living in 11 other developed countries. This highlights that social determinants of health (SDH) likely contribute to disparities in LN outcomes in the US. However, the overall burden of adverse SDHs on LN outcomes and how each SDH domain contributes to observed health disparities have not been fully examined. In the absence of such information, health disparities between racial/ethnic groups may be interpreted as inherently "biological" or "cultural" differences. Thus, there is a need to understand the underlying mechanisms explaining how SDHs influence outcomes and contribute to health disparities in LN to advance equity. Objectives of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to: 1) determine the odds of poor LN outcomes in patients with i) any adverse SDHs, and ii) specific SDH domains; 2) develop a framework for the multidimensional impact of SDH on LN outcomes.

Methods: A comprehensive search was performed using MeSH headings and keywords (e.g., lupus nephritis, insurance, poverty, neighborhood socio-economic status, death, etc.) in Medline, Embase, CINAHL and Web of Science. We included observational and interventional studies on human subjects measuring associations between SDHs and LN outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using standard tools for all studies.

We examined pooled odds of severe LN outcomes (primary outcome) including mortality, end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), or cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with and without any adverse SDHs using a random effects model. Additionally, we calculated the pooled odds of poor outcomes by each SDH domain: individual (e.g., race, insurance), healthcare (e.g., fragmented care, hospital experience), community (e.g., neighborhood socioeconomic status), and behavioral (e.g., smoking) (Fig. 1). Heterogeneity was assessed using I2.

Results: Among 531 manually reviewed abstracts, 31 met inclusion. Only 13 studies comparing LN outcomes in patients with and without adverse SDHs were included in the meta-analysis. Overall 92% of studies had low risk of bias. The pooled odds of poor outcomes (death, ESKD, or CVD) in patients with any adverse SDHs were 45% higher compared to those without any adverse SDHs (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.10-1.91, p = 0.008, I2 85%, Fig. 2). Among the four SDH domains, 64% and 77% higher odds of poor outcomes were noted in patients with adverse SDHs in individual and healthcare domains (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.13-2.39, I2 92%; OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.2-3.0, I2 0%; Fig. 3A-D). Our framework highlighted a multiplicative impact of adverse SDHs in different domains on poor LN outcomes (Fig. 1). As illustrated in Fig. 1, patients of Black race with fragmented care and public insurance had 12-fold higher odds of mortality/ESKD.

Conclusion: Our study reports a strong negative impact of adverse SDHs on LN outcomes, with the worst impact in patients with adverse individual and healthcare SDH domains. Moreover, having adverse SDHs in ≥2 domains had a multiplicative impact leading to 12-fold higher odds of poor outcomes, widening health disparities in LN. These findings could guide future health-equity focused interventions to address outcome disparities in LN.

.jpg)

Fig. 1 Conceptual model highlighting the impact of adverse individual, community, healthcare, and behavioral SDHs on severe LN outcomes. Data in row B. illustrate multiplicative effects of SDH on LN outcomes.

Fig. 2. Forest plot showing the odds of ESKD or death in patients with or without any adverse social determinants of health

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the odds of ESKD or death with or without adverse social determinants of health in each SDH domain

S. Garg: None; B. Boderman: None; N. Sweet: None; D. Montes: None; B. Astor: None; S. Lim: None; C. Bartels: Pfizer, 5.